ethnopoetics

discourses

ethnopoetics

discourses  ethnopoetics

home

ethnopoetics

home  ubuweb

ubuweb

TOTAL TRANSLATION: AN EXPERIMENT IN THE TRANSLATION OF AMERICAN INDIAN POETRY

Jerome Rothenberg

It wasn't really a "problem," as these things are sometimes called, but to get closer to a way of poetry that had concerned me from years before, though until this project I'd only been able to approach it at a far remove. I'd been translating "tribal" poetry (the latest, still imperfect substitute I can find for "primitive," which continues to bother me) out of books; doing my versions from earlier translations into languages I could cope with, including English. Toward the end of my work on Technicians I met Stanley Diamond, who directed me to the Senecas in upstate New York, & David McAllester, ethno-- musicologist at Wesleyan University, who showed me how a few songs worked in Navajo. With their help (& a nod from Dell Hymes as well) I later was able to get Wenner--Gren Foundation support to carry on a couple of experiments in the translation of American Indian poetry. I'm far enough into them by now to say a little about what I've been doing.

* * *

In the Summer of 1968 I began to work simultaneously with two sources of Indian poetry. Settling down a mile from the Cold Spring settlement of the Allegany (Seneca) Reservation at Steamburg, New York, I was near enough to friends who were traditional songmen to work with them on the translation of sacred & secular song--poems. At the same time David McAllester was sending me recordings, transcriptions, literal trans-- lations & his own freer reworkings of a series of seventeen "Horse Songs" that had been the property of Frank Mitchell, a Navajo singer from Chinle, Arizona (born: 1881, died: 1967). Particularly with the Senecas (where I didn't know in the first instance what, if anything, I was going to get) my first concern was with the translation process itself. While I'll limit myself to that right now, I should at least say (things never seem to be clear unless you say them) that if I hadn't also come up with matter that I could "internalize," I would have foundered long before this.

The big question, which I was immediately aware of with both poetries, was if & how to handle those elements in the original works that weren't translatable literally. As with most Indian poetry, the voice carried many sounds that weren't, strictly speaking, "words." These tended to disappear or be attenuated in translation, as if they weren't really there. But they were there & were at least as important as the words themselves. In both Navajo & Seneca many songs consisted of nothing but those "meaningless" vocables (not free "scat" either but fixed sounds recurring from performance to performance). Most other songs had both meaningful & non--meaningful elements, & such songs (McAllester told me for the Navajo) were often spoken of, qua title, by their meaningless burdens. Similar meaningless sounds, Dell Hymes had pointed out for some Kwakiutl songs, might in fact be keys to the songs' structures: "something usually disregarded, the refrain or so--called 'nonsense syllables' . . . in fact of fundamental importance . . . both structural clue & microcosm."

So there were all these indications that the exploration of "pure sound" wasn't beside the point of those poetries but at or near their heart: all of this coincidental too with concern for the sound--poem among a number of modern poets. Accepting its meaning-- fulness here, I more easily accepted it there. I also realized (with the Navajo especially) that there were more than simple refrains involved: that we, as translators & poets, had been taking a rich oral poetry & translating it to be read primarily for meaning, thus denuding it to say the least.

Here's an immediate example of what I mean. In the first of Frank Mitchell's seventeen Horse Songs, the opening line comes out as follows in McAllester's transcription:

dzo--wowode sileye shi, dza--na desileye shiyi dzanadi sileye shiya'e

but the same segment given "as spoken" reads:

dz____di silá shi dz____di silá shi dz____di silá shi

which translates as "over--here it--is--there--(&) mine" repeated three times. So does the line as sung if all you're accounting for is the meaning. In other words, translate only for meaning & you get the three--fold repetition of an unchanging single statement; but in the Navajo each time it's delivered there's a sharp departure from the spoken form: thus three distinct sound--events, not one--in--triplicate!

I know neither Navajo nor Seneca except for bits of information picked up from grammar books & such (also the usual social fall--out among the Senecas: "cat," "dog," "thank you," "you're welcome," numbers one to ten, "uncle," "father," & my Indian name). But even from this far away, I can (with a little help from my friends) be aware of my options as translator. Let me try, then, to respond to all the sounds I 'm made aware of, to let that awareness touch off responses or events in the English. I don't want to set English words to Indian music, but to respond poem--for--poem in the attempt to work out a "total" translation --not only of the words but of all sounds connected with the poem, including finally the music itself.

* * *

Seneca & Navajo are very different worlds, & what's an exciting procedure for one may be deadening or irrelevant for the other. The English translation should match the character of the Indian original: take that as a goal & don't worry about how literal you're otherwise being. Walter Lowenfels calls poetry "the continuation of journalism by other means," & maybe that holds too for translation--as--poem. I translate, then, as a way of reporting what I've sensed or seen of an other's situation: true as far as possible to "my" image of the life & thought of the source.

Living with the Senecas helped in that sense. I don't know how much stress to put

on this, but I know that in so far as I developed a strategy for translation from Seneca, I tried to keep to approaches I felt were consistent with their way of life as I observed it. I can hardly speak of the poetry without using words that would describe the people as well. Not that it's easy to sum--up any people's poetry or its frame--of--mind, but since one is always doing it in translation, I'll attempt it also by way of description.

Seneca poetry,1 when it uses words at all, works in sets of short song, minimal realizations colliding with each other in marvelous ways, a very light, very pointed play--of--the--mind, nearly always just a step away from the comic (even as their masks are), the words set out in clear relief against the ground of the ("meaningless") refrain. Clowns stomp & grunt through the longhouse, but in subtler ways too the encouragement to "play" is always a presence. Said the leader of the longhouse religion at Allegany, explaining why the seasonal ceremonies ended with a gambling game: the idea of a religion was to reflect the total order of the universe while providing an outlet for all human needs, the need for play not least among them. Although it pretty clearly doesn't work out as well nowadays as that makes it sound -- the orgiastic past & the "doings" (happenings) in which the people were free to live--out their dreams dimming from generation to generation -- still the resonance, the ancestral permissiveness, keeps being felt in many ways. Sacred occasions may be serious & necessary, but it doesn't take much for the silence to be broken by laughter: thus, says Richard Johnny John, if you call for a medicine ceremony of the mystic animals & it turns out that no one's sick & in need of curing, the head--one tells the others: "I leave it up to you folks & if you want to have a good time. have a good time!" He knows they will anyway.

I take all of that as cue: to let my moves be directed by a sense of the songs & of the attitudes surrounding them. Another thing I try not to overlook is that the singers & I, while separated in Seneca, are joined in English. That they have to translate for me is a problem at first, but the problem suggests its own solution. Since they're bilingual, sometimes beautifully so, why not work from that instead of trying to get around it? Their English, fluent while identifiably Senecan, is as much a commentary on where they are as mine is on where I am. Given the "minimal" nature of much of the poetry (one of its strongest features, in fact) there's no need for a dense response in English. Instead I can leave myself free to structure the final poem by using their English as a base: a particular enough form of the language to itself be an extra means for the extension of reportage through poetry & translation.

I end up collaborating & happy to do so, since translation (maybe poetry as well) has always involved that kind of thing for me. The collaboration can take a number of forms. At one extreme I have only to make it possible for the other man to take over: in this case, to set up or simply to encourage a situation in which a man who's never thought of himself as a "poet" can begin to structure his utterances with a care for phrasing & spacing that drives them toward poetry. Example: Dick Johnny John & I had taped his Seneca version of the thanking prayer that opens all longhouse gatherings & were translating it phrase by phrase. He had decided to write it down himself, to give the translation to his sons, who from oldest to youngest were progressively losing the Seneca language. I could follow his script from where I sat, & the method of punctuation he was using seemed special to me, since in letters & such he punctuates more or less conven-- tionally. Anyway, I got his punctuation down along with his wording, with which he was taking a lot of time both in response to my questions & from his desire "to word it just the way it says there." In setting up the result, I let the periods in his prose version mark the ends of lines, made some vocabulary choices that we'd left hanging, & tried for the rest to keep clear of what was after all his poem. Later I titled it Thank You: A Poem in 17 Parts, & wrote a note on it for the Mexico City magazine El Corno Emplumado, where it was printed in English & Spanish. This is the first of the seventeen sections:

Now so many people that are in this place.

In our meeting place.

It starts when two people see each other.

They greet each other.

Now we greet each other.

Now he thought.

I will make the Earth where some people can walk around.

I have created them, now this has happened.

We are walking on it.

Now this time of the day.

We give thanks to the Earth.

This is the way it should be in our minds.

[ Note. The set--up in English doesn't, as far as I can tell, reproduce the movement of the Seneca text. More interestingly it's itself a consideration of that movement: is in fact Johnny John's reflections upon the values, the relative strengths of elements in his text. The poet is to a great degree concerned with what--stands--out & where, & his phrasing reveals it, no less here than in any other poem.]

Even when being more active myself, I would often defer to others in the choice of words. Take, for example, a set of seven Woman's Dance songs with words, composed by Avery Jimerson & translated with help from his wife, Fidelia. Here the procedure was for Avery to record the song, for Fidelia to paraphrase it in English, then for the three of us to work out a transcription & word--by--word translation by a process of question & answer. Only afterwards would I actively come into it, to try to work out a poem in English with enough swing to it to return more or less to the area of song. Example. The paraphrase of the 6th Song reads:

Very nice, nice, when our mothers do the ladies' dance. Graceful,

nice, very nice, when our mothers do the ladies' dance . . .

while the word--by--word, including the "meaningless" refrain, reads:

hey heya yo oh ho

nice nice nice--it--is

when--they--dance--the--ladies--dance

our--mothers

gahnoweyah heyah

graceful it--is

nice nice nice--it--is

when--they--dance--the--ladies--dance

our--mothers

gahnoweyah heyah (& repeat).

In doing these songs, I decided in fact to translate for meaning, since the meaningless vocables used by Jimerson were only the standard markers that turn up in all the woman's songs: hey heyah yo to mark the opening, gahnoweyah heyah to mark the internal transitions. (In my translation, I sometimes use a simple "hey," "oh" or "yeah" as a rough equivalent, but let the movement of the English determine its position.) I also decided not to fit English words to Jimerson's melody, regarding that as a kind of oil--&--water treatment, but to suggest (as with most poetry) a music through the normally pitched speaking voice. For the rest I was following Fidelia Jimerson's lead:

hey it's nice it's nice it's nice

to see them yeah to see

our mothers do the ladies' dances

oh it's graceful & it's

nice it's nice it's very nice

to see them hey to see

our mothers do the ladies' dances

With other kinds of song--poems I would also, as often as not, stick close to the translation--as--given, departing from that to better get the point of the whole across in English, to normalize the word order where phrases in the literal translation appeared in their original Seneca sequence, or to get into the play--of--the--thing on my own. The most important group of songs I was working on was a sacred cycle called Idos (ee--dos) in Seneca -- in English either Shaking the Pumpkin or, more ornately, The Society of the Mystic Animals. Like most Seneca songs with words (most Seneca songs are in fact without words), the typical Pumpkin song contains a single statement, or a single statement alternating with a row of vocables, which is repeated anywhere from three to six or seven times. Some songs are nearly identical with some others (same melody & vocables, slight change in words) but aren't necessarily sung in sequence. In a major portion of the ceremony, in fact, a fixed order for the songs is completely abandoned, & each person present takes a turn at singing a ceremonial (medicine) song of his or her own choice. There's room here too for messing around.

Dick Johnny John was my collaborator on the Pumpkin songs, & the basic wording is therefore his. My intention was to account for all vocal sounds in the original but --as a more "interesting" way of handling the minimal structures & allowing a very clear, very pointed emergence of perceptions --to translate the poems onto the page, as with "concrete" or other types of "minimal" poetry. Where several songs showed a concur-- rence of structure. I allowed myself the option of treating them individually or combin-- ing them into one. I deferred singing until some future occasion.

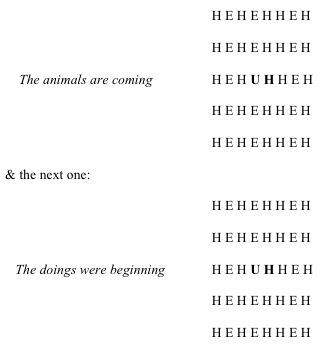

Take the opening songs of the ceremony. These are fixed pieces sung by the ceremonial leader (hajaswas) before he throws the meeting open to the individual singers. The melody & structure of the first nine are identical: very slow, a single line of words ending with a string of sounds, etc., the pattern identical until the last go--round, when the song ends with a grunting expulsion of breath into a weary "ugh" sound. I had to get all of that across: the bareness, the regularity, the deliberateness of the song, along with the basic meaning, repeated vocables, emphatic terminal sound, & (still following Johnny John's reminder to play around with it "if everything's alright") a little something of my own. The song whose repeated line is:

The animals are coming heh eh heh (or heh eh--eh--eh he) can then become:

& so forth: each poem set, if possible, on its own page, as further analogue to the slowness, the deliberate pacing of the original.

The use of vertical titles is the only move I make without immediate reference to the Seneca version: the rest I'd feel to be programmed by elements in the original prominent enough for me to respond to in the movement from oral to paginal structure. Where the song comes without vocables, I don't supply them but concentrate on presentation of the words. Thus in the two groups of "crow songs," the first is a simple translation--for--meaning:

(1)

the crows came in

(2)

the crows sat down

while the other ("in the manner of Zukofsky" [i.e. his translations of Catullus]) puns

off the Seneca sound:

yehgagaweeyo (lit. that pretty crow) becomes "yond cawcrow's way--out'

&

hongyasswahyaenee (lit. that [pig]--meat's for me) becomes "Hog (yes!) swine

you're mine"

trying at the same time to let something of the meaning come through.

A motive behind the punning was, I suppose, the desire to bring across (i.e. "translate") the feeling of the Seneca word for crow (gaga or kaga), which is at the same time an imitation of the bird's voice. In another group -- three songs about the owl -- I pick up the vocables suggesting the animal's call & shape them into outline of a giant owl, within which frame the poems are printed. But that's only where the mimicry of the original is strong enough to trigger an equivalent move in translation; otherwise my inclination is to present analogues to the full range of vocal sound, etc., but not to represent the poem's subject as "mere picture."

The variety of possible moves is obviously related to the variety -- semantic &

aural -- of the cycle itself.

[Note. Behind it all there's a hidden motive too: not simply to make clear the world of the original, but to do so at some remove from the song itself: to reflect the song without the "danger" of presenting any part of it (the melody, say) exactly as given: thus to have it while not having it, in deference to the sense of secrecy & localization that's so important to those for whom the songs are sacred & alive. So the changes resulting from translation are, in this instance, not only inevitable but desired, or, as another Seneca [Art Johnny John] said to me: "We wouldn't want the songs to get so far away from us; no, the songs would be too lonely."]

* * *

My decision with the Navajo Horse Songs was to work with the sound as sound: a reflection in itself of the difference between Navajo & Seneca song structure. For Navajo (as already indicated) is much fuller, much denser, twists words into new shapes or fills up the spaces between words by insertion of a wide range of "meaningless" vocables, making it misleading to translate primarily for meaning or, finally, to think of total translation in any terms but those of sound. Look, for example, at the number of free vocables in the following excerpt from McAllester's relatively literal translation of the 16th Horse Song:

(nana na) Sun-- (Yeye ye) Standing--within (neye ye) Boy

(Heye ye) truly his horses

('Eye ye) abalone horses

('Eye ye) made of sunrays

(Neye ye) their bridles

(Gowo wo) coming on my right side

(Jeye yeye) coming into my hand (yeye neyowo 'ei).

Now this, which even so doesn't show the additional word distortions that turn up in the singing, might be brought closer to English word order & translated for meaning alone as something like

Boy who stands inside the Sun

with your horses that are

abalone horses

bridles

made of sunrays

rising on my right .side

coming to my hand

etc.

But what a difference from the fantastic way the sounds cut through the words & between them from the first line of the original on.

It was the possibility of working with all that sound, finding my own way into it in English, that attracted me now --that & a quality in Frank Mitchell's voice I found irresistible. It was, I think, that the music was so clearly within range of the language: it was song & it was poetry, & it seemed possible at least that the song issued from the poetry, was an extension of it or rose inevitably from the juncture of words & other vocal sounds. So many of us had already become interested in this kind of thing as poets, that it seemed natural to me to be in a situation where the poetry would be leading me toward a (new) music it was generating.

I began with the 10th Horse Song, which had been the first one Mitchell sang when McAllester was recording him. At that point I didn't know if I'd do much more than quote or allude to the vocables: possibly pull them or something like them into the English. I was writing at first, working on the words by sketching in phrases that seemed natural to my own sense of the language. In the 10th Song there's a division of speakers: the main voice is that of Enemy Slayer or Dawn Boy, who first brought horses to The People, but the chorus is sung by his father, the Sun, telling him to take spirit horses & other precious animals & goods to the house of his mother, Changing Woman. The literal translation of the refrain -- (to) the woman, my son --seemed a step away from how we'd say it, though normal enough in Navajo. It was with the sense that, whatever distortions in sound the Navajo showed, the syntax was natural, that I changed McAlles-- ter's suggested reading to go to her my son, & his opening line:

Boy--brought--up--within--the--Dawn, it is I, I who am that one

(lit. being that one, with a suggestion of causation), to:

Because I was the boy raised in the dawn.

At the same time I was, I thought, getting it down to more or less the economy of phrasing of the original.

I went through the first seven or eight lines like that but still hadn't gotten to the vocables. McAllester's more "factual" approach -- reproducing the vocables exactly -- seemed wrong to me on one major count. In the Navajo the vocables give a very clear sense of continuity from the verbal material; i.e., the vowels in particular show a rhyming or assonantal relationship between the "meaningless" & meaningful segments:

'Esdza shiye' e hye--la 'Esdza shiye' e hye--la ŋaŋa yeye Ôe

The woman, my son (voc.) The woman, my son (voc.)

whereas the English words for this & many other situations in the poem are, by contrast to the Navajo, more rounded & further back in the mouth. Putting the English words ("son" here but "dawn," "home." "upon," "blown," etc. further on) against the Navajo vocables denies the musical or sonic coherence of the original & destroys the actual flow. I decided to translate the vocables & from that point on was already playing with the possibility of translating other elements in the songs not usually handled by translation. It also seemed important to get as far away as I could from writing. So I began to speak, then sing my own words over Mitchell's tape, replacing his vocables with sounds relevant to me, then putting my version on a fresh tape, having now to work it in its own terms. It wasn't an easy thing either for me to break the silence or go beyond the narrow pitch levels of my speaking voice, & I was still finding it more natural in that early version to replace the vocables with small English words (it's hard for a word--poet to lose words completely), hoping some of their semantic force would lessen with reiteration:

Go to her my son & one & go to her my son & one & one & none & gone

Go to her my son & one & go to her my son & one & one & none & gone

Because I was the boy raised in the dawn & one & go to her my son & one & one &

none & gone

& leaving from the house the bluestone home & one & go to her my son & one & one

& one & none & gone

& leaving from the house the shining home & one & go to her my son & one & one &

none & gone

& from the swollen house my breath has blown & one & go to her my son & one & one

& none & gone

& so on. In the transference too à likely enough because my ear is so damn slow à I

found I was considerably altering Mitchell's melody; but really that was part of the

translation process also: a change responsive to the translated sounds & words I was

developing.

In singing the 10th Song I was able to bring the small words (vocable substitutions) even further into the area of pure vocal sound (the difference, if it's clear from the spelling, between one, none & gone and wnn, nnnn & gahn): soundings that would carry into the other songs at an even greater remove from the discarded meanings.2 What I was doing in one sense was contributing & then obliterating my own level of meaning, while in another sense I was as much as recapitulating the history of the vocables themselves, at least according to one of the standard explanations that sees them as remnants of archaic words that have been emptied of meaning: a process I could still sense elsewhere in the Horse Songs -- for example, where the sound howo turns up as both a "meaningless" vocable & a distorted form of the word hoghan = house. But even if I was doing something like that in an accelerated way, that wasn't the real point of it for me. Rather what I was getting at was the establishment of a series of sounds that were assonant with the range of my own vocabulary in the translation, & to which I could refer whenever the Navajo sounds for which they were substitutes turned up in Mitchell's songs.

In spite of carryovers, these basic soundings were different for each song (more specifically, for each pair of songs), & I found, as I moved from one song to another, that I had to establish my sound equivalencies before going into the actual translation. For this I made use of the traditional way the Navajo songs begin: with a short string of vocables that will be picked up (in whole or in part) as the recurring burden of the song. I found I could set most of my basic vocables or vocable--substitutes into the opening, using it as a key to which I could refer when necessary to determine sound substitutions, not only for the vocables but for word distortions in the meaningful segments of the poems. There was a cumulative effect here too. The English vocabulary of the 10th Song -- strong on back vowels, semivowels, glides & nasals -- influenced the choice of vocables: the vocables influenced further vocabulary choices & vocables in the other songs. (Note. The vocabulary of many of the songs is very close to begin with, the most significant differences in "pairs" of songs coming from the alternation of blue & white color symbolism.) Finally, the choice of sounds influenced the style of my singing by setting up a great deal of resonance I found I could control to serve as a kind of drone behind my voice. In ways like this the translation was assuming a life of its own.

With the word distortions too, it seemed to me that the most I should do was approximate the degree of distortion in the original. McAllester had provided two Navajo texts --the words as sung & as they would be if spoken --& I aimed at roughly the amount of variation I could discern between the two. I further assumed that every perceivable change was significant, & there were indications in fact of a surprising degree of precision in Mitchell's delivery, where even what seemed to be false steps or accidents might really be gestures to intensify the special or sacred powers of the song at the points in question. Songs 10 & 11, for example, were structurally paired, & in both songs Mitchell seemed to be fumbling at the beginning of the 21st line after the opening choruses. Maybe it was accidental & maybe not, but I figured I might as well go wrong by overdoing the distortion, here & wherever else I had the choice.

So I followed where Mitchell led me, responding to all moves of his I was aware of & letting them program or initiate the moves I made in translation. All of this within obvious limits: those imposed by the field of sound I was developing in English. Throughout the songs I've now been into, I've worked in pretty much that way: the relative densities determined by the original, the final form by the necessities of the poem as it took shape for me. Obviously too, there were larger patterns to keep in mind, when a particular variation occurred in a series of positions, etc. To say any more about that -- though the approach changed in the later songs I worked on, toward a more systematic handling -- would be to put greater emphasis on method than any poem can bear. More important for me was actually being in the stimulus & response situation, certainly the most physical translation I've ever been involved in. I hope that that much comes through for anyone who hears these sung.

But there was still another step I had to take. While the tape I was working from was of Mitchell singing by himself, in actual performance he would be accompanied by all those present with him at the blessing. The typical Navajo performance pattern, as McAllester described it to me, calls for each person present to follow the singer to whatever degree he can. The result is highly individualized singing (only the ceremonial singer is likely to know all of it the right way) & leads to an actual indeterminacy of performance. Those who can't follow the words at all may make up their own vocal sounds -- anything, in effect, for the sake of participation.

I saw the indeterminacy, etc., as key to the further extension of the poems into the area of total translation & total performance. (Instrumentation & ritual--events would be further "translation" possibilities, but the Horse Songs are rare among Navajo poems in not including them.) To work out the extension for multiple voices, I again made use of the tape recorder, this time of a four--track system on which I laid down the following as typical of the possibilities on hand:

TRACK ONE. A clean recording of the lead voice.

TRACK TWO. A voice responsive to the first but showing less word distortion &

occasional free departures from the text.

TRACK THREE. A voice limited to pure--sound improvisations on the meaning--

less elements in the text.

TRACK FOUR. A voice similar to that on the second track but distorted by means of a violin amplifier placed against the throat & set at "echo" or "tremolo." To be used only as a barely audible background filler for the others.

Once the four tracks were recorded I had them balanced & mixed onto a monaural tape. In that way I could present the poems as I'd conceived them & as poetry in fact had always existed for men like Mitchell -- to be heard without reference to their incidental appearance on the page.3

* * *

Translation is carry--over. It is a means of delivery & of bringing to life. It begins with a forced change of language, but a change too that opens up the possibility of greater understanding. Everything in these song--poems is finally translatable: words, sounds, voice, melody, gesture, event, etc., in the reconstitution of a unity that would be shattered by approaching each element in isolation. A full & total experience begins it, which only a total translation can fully bring across.

By saying which, I'm not trying to coerce anyone (least of all myself) with the idea of a single relevant approach to translation. I'll continue, I believe, to translate in part or in any other way I feel moved to, nor would I deny the value of handling words or music or events as separate phenomena. It's possible too that a prose description of the song--poems, etc., might tell pretty much what was happening in & around them, but no amount of description can provide the immediate perception that translation can. One way or other translation makes a poem in this place that's analogous in whole or in part to a poem in that place. The more the translator can perceive of the original -- not only the language but, more basically perhaps, the living situation from which it comes &, very much so, the living voice of the singer -- the more of it he should be able to deliver. In the same process he will be presenting something -- i.e.. making something present, or making something as a present -- for his own time & place.

source: Jerome Rothenberg, Pre--Faces & Other Writings, New Directions, 1981. For audio of Jerome Rothenberg's Six Horse Songs for Four voices, go to https://www.ubu.com/sound/rothenberg.html.

notes

1 By poetry in what follows, I am largely speaking of the words of song, both sacred & secular, including the word-like but non-semantic vocables.

2 The translation of the First Horse Song shows the final version clearly & fully. The opening line of the 10th Horse Song (after the refrain) changes from the version given above to read: Because I was thnboyngnng raised ing the dawn NwnnN go to her my son N wnn N wnn N nnnn N gahn.Ó

3 A final recorded version composed along somewhat altered lines appeared nearly ten years after the essay as 6 Horse Songs for 4 Voices (New Wilderness Audiographics, 1978). It is currently available on the Ubuweb web site: https://www.ubu.com/sound/ along with a number of other performance works.

.