| << UbuWeb |

| Aspen no. 4, item 8 |

|

|

| Psycles |

|

|

* Bob Dylan © 1966 M. Whitmark & Sons

|

Funny looks at intersections, or out of side windows as I pass. Anywhere else in the world people wouldn't even turn around. But then nobody's ever ridden through Europe forty at a time on chopped Harleys with full leathers and swastikas. Maybe somebody should. Right through Germany, helmets and iron crosses, right down the Autobahn to Berlin with flags and signs like "Buy American"; wheelies through Checkpoint Charlie, and rock & roll street dances in East Berlin with tapes of The Mamas & Papas "California Dreamin'", declare the place Sister City to Hollister. But my friend says it's not true everyone on two wheels has something in common, even after I show him Life's spread on Russia, with that fantastic color shot of Sunday afternoon dirt-track scrambles in Siberia. Maybe he's right. You don't always meet the nicest people on a Triumph. But people freak-out over nothing—grease, cigars, hair, noise. Tattoos. Dew-rags. "HATE" is a freak put-on. Amphetamine and "ripple". Bob Dylan bumped his head and Richard Farina burned, so Time says motorcycles are status symbols. Funny kind of status; I'll never get trapped inside a car again waiting single-file in endless lines of four-wheeled houses too awkward to do anything but sit there sniffing the other guy's exhaust pipe listening to FM, thinking I'm not here it doesn't exist or both. Ten lanes of concrete crawling at twenty mph, and still everybody thinks more pavement is the way out. McLuhan says the automobile is obsolescent and people gasp. Four wheels and booze, job and marriage, horse and carriage. "The old men don't realize, but the little girls understand."** They're the ones that smile at intersections. Little kids and sometimes grandmothers, fascination, envy; in small towns in Nevada maybe a broken-down man pumping gas tells me of travelling on vintage Harleys with a stunt-rider show while local kids on Hondas check out my rig. Farm kid in Utah chases me down outside of town to find out where I'm going and where I've been. Motel owner's daughter talks vaguely of Reno, mythically of San Francisco. Am I that free? Powering up, bouncing over rocks, spinning, sliding through ruts, gravel, working the slope, skiing uphill, standing on the pegs, hanging on to full throttle. Ride through open fields of tall grass, jumping half-sunken boulders, fanning out in all directions. Fast and in tight together through the woods, trees flashing past, branches overhead. Out into open meadows of alpine flowers, sky, clouds, sun. Rain and mud, deep puddles with feet up for the splash. Wheelie-jumps out of an old mine pit into the air and then down fast, stay tight with the man ahead, follow his line, never mind what's over the edge, power on. Back to town, wet and steaming, machine thick with mud, a piece of green weed and purple flower caught in the forks. — Bob Chamberlain |

|

Danny Lyon was a member of the Chicago Outlaws for a year. The Outlaw photographs and taped conversations reproduced here were made during that time, and are from his forthcoming book, The Bikeriders, to be published by The MacMillan Co.

So much has been written about outlaw bike riders recently, that the published material long ago surpassed the reality it claimed to deal with. Outlaw bike clubs are not new. Ten years ago their members already were living imitations of themselves on television. What is "new" is that lately everything about motorcycles has become commercially valuable, including talk, so we have been experiencing a great deal of it. The talk has not been directly fabricated, but it falls on ears so anxious to hear it that it becomes in effect the cause of the subject portrayed. Interest in my book, "The Bikeriders," often centers on the question of Hell's Angels type riders. The H.A. style, while once genuine, so thrived on the publicity it received that eventually it was murdered by it. To me, the only phenomenon left about the H.A.'s is how much the communications industry loves them. Feeding the intellectual's search for the noble savage, they cavort in the national spotlight. I was interested in bike riders as people, not actors, and I believe there is something more and very rich in the people of the outlaw bike world, and even in the H.A.'s who haven't given everything over to their acting careers. |

|

People have been taken with motorcycles since they first appeared in America over fifty years ago. From this fascination developed the motorcycle legend — a legend that crystallized during the July 4, 1947 weekend at Hollister, Calif., at the first gypsy tour held after the war. What actually happened that weekend was probably never very clear to most of the participants, but at some point the bonanza business in the taverns (stools had been removed so cyclists could ride in for drinks) erupted into trouble with the police. Here is one participant's version which is as interesting and unreliable as any. Jack Halferty, a Chicago motorcycle mechanic in Hollister that weekend, remembers that the bars were making lots of money and most everyone was having a good time when the "incident" occurred that started the "riot." Jack remembers that a rider was tuning his machine on somebody's front lawn when a volunteer officer insisted he move his bike (auxiliaries had been added to Hollister's seven-man police force). The rider refused "and the yoyo drew his gun." The cyclist swept his chick from the back of his bike, drove at the cop, and throwing his machine into a slide, ran the cop down. Within minutes, an out-of-town police car arrived (with a bulletproof grill over the radiator) and soon police were grabbing everything that moved. They raced through Hollister arresting everyone in sight and throwing motorcycles into the backs of trucks. "After that you saw nothing but riot guns and goodby Charlie. There were bike tracks everywhere. Everyone was trying to get out. One guy went right through a white wood fence."

Two weeks later, Life magazine covered "The Sack of Hollister" with a 110-word caption and a full-page picture of a bike rider with a beer in his hand ("Cyclist's Holiday — He and friends terrorize a town"). Then Frank Rooney used the incident for a short story. And that became the basis for Stanley Kramer's movie, |

|

|

While Brando rode the movie theater screens, the radio kept playing the Cheers recording of "Black Denim Trousers and Motorcycle Boots." In it, the hero (whose arm is tattooed with an eagle saying "Mother I love you") tries to beat a freight train to a crossing on his bike and is never heard from again. Ten years ago, the song celebrated the bike rider that had already been on the road for years. It is often a surprise to the viewers of these pictures that outlaw motorcyclists do such things as have meetings, live in houses, and on occasion, get married and have children. Bike riders, being people, do all these things. But you can't categorize them accurately about anything. Some have jobs, and some don't. Corky worked at R. R. Donnelley for a long time, drove a cab, and worked at a Jewish cemetery until he was fired for laughing during services. Some, like Johnny (who has two teen-age daughters) and Big Jim, live in comfortable middle-class homes. Others like Cal and Funny Sonny have left wives and children in California and usually have to borrow money to put gasoline in their motorcycles. One bike rider is different from another, and their bond is that for each of them, the motorcycle has been important in their lives. I now realize that there are no motorcycle gangs, just different kinds of clubs. Most clubs receive their sanction from the A.M.A. (American Motorcycle Assn.), the organization that oversees most of the racing and motorcycling activity (field meets, rodeos, gypsy tours, and a few motorcycle blessings). The organization, whose motto is "Put your best wheel forward," urges its members to be good citizens, obey all traffic laws, and use legal mufflers, among other things. Its membership cards carry a quote by J. Edgar Hoover, introduced as "famed head of the F.B.I.," reminding cyclists to be careful on the highway.

|

|

Some clubs fail to receive the A.M.A. sanction because their attitude is not in keeping with the spirit of the A.M.A. These are known as outlaw clubs. Wives and girl friends of the members of outlaw clubs have been known to sew the A.M.A. emblem on the seat of their pants.

I joined the Outlaws with a girl (my swinger) and we were accepted by the members with an affection that we returned and which still goes on. Eddie, Johnny, Kathy, and all of them were our friends and more than that we all lived within the bond of being Chicago Outlaws. Cal wears a ring that my old lady gave him, and I still wear a leather jacket that Cal's father gave to him. Cal and I share a set of earrings. When I first met Kid from the Pagans we spent a whole day together and got on very well. Later he gave me a small imitation Nazi war medal. That meant he liked me. To me, the Outlaws were people and bike riders, and nothing else about them impressed me to the extent that those things did. The ideology of Obnoxiousness in a chrome Nazi helmet is not very meaningful when you see it close up; and had I been only interested in that, I might have better spent the time infiltrating high-school fraternities. If someone like Sonny or Cockroach could refine bug eating to the high art they did, then I could only dig them for it. But if the antics were obviously bad copies of bad magazine stories, or the ideology only appeared when a reporter asked for a statement of purpose, I failed to be moved by it. Racers are not outlaws. Many racers are openly hostile to outlaws because of the kind of publicity outlaws bring to motorcycling and the fact that their activity occasionally disrupts races. (The big events for the outlaw clubs are the runs to the national championship races — $10 fine if you don't show and $5 if you come by car — but nobody cares too much about the races, but much more about partying with their friends from other outlaw clubs.) Johnny Goodpaster is not an outlaw but one of the best scrambles racers in the Midwest. An ex-paratrooper, Goodpaster runs a motorcycle shop in Hobart, Indiana, with his wife. Of his five kids, the two oldest boys race and the eight-year-old is already riding his own motorcycle. Goodpaster has won over 500 trophies in the last ten years and on occasion forgets to pick them up after a race. |

|

|

Cockroach was one of the first Outlaws to befriend me when I joined the club, which meant he talked to me right away while some of the others waited until they had seen me twice. He was delighted that I was a photographer, disclosing that his great ambition was to have his picture in a book captioned as a barbarian. He wanted to be able to show it to his son. "If you look at history," Cockroach said, "the barbarians always come out on top." Cockroach is no longer with the club with conflicting reasons given. The official story is that he fired a shotgun in his house (accidently) and his wife and mother tried to have him committed so he ran away. But I remember one night when one of the Outlaws came up to me very drunk and sad and told me that Cockroach was a big phoney, and ate bugs only after Sonny and others showed him how, and that the story about the shotgun story was invented so Cockroach could get out of the club. Leaving the club is often a sensitive issue, so the circumstances of a departure often are clouded in confusion. Eddie also is no longer with the club. He had the misfortune of being caught in a police raid on the Coach House, one of the club's hang-outs, and becoming the subject of a newspaper story headlined, "Dope, Nazi Flags Seized."

Funny Sonny was a Hell's Angel for a number of years before he moved to the Midwest, and he organized a small outlaw club of his own before he joined the Chicago Outlaws. Sonny is a kind of an independent and something of a club-hopper. You're not supposed to leave California with your Angel patch, but Sonny's is always close by, in case the press demands it. He swears eternal loyalty to Chicago, then one day wanders off to Columbus, Ohio, where he dons their patch. Things get boring there, so he borrows gas money to go to Milwaukee. There, with a meeting of 200 Outlaws going on, Sonny gives a TV interview in his Angel colors and terrifies the town. Rumors of hordes of Hell's Angels (Sonny) puts the heat on the club, so Funny Sonny returns to Chicago and begs to be re-admitted, which he is. Then "The Wild Angels" movie opens in Chicago, and for $10 a day Sonny dons Angel colors and sits menacingly outside the theater on his CH. That's too much for everyone, for the patch is taken seriously, and Sonny is thrown out again. I don't know right now if Funny Sonny is back in or back out. The first night I went to an Outlaw meeting, Kathy was there. What I didn't realize then was that the club was new for her too. The girl's world in the club is really separate, open to my swinger, but not to me. When the club meets in a back room of a bar, the wives, swingers, and camp followers wait out front, doing far-out things like dancing together or fixing their hair. Kathy and other women in the club had a way of knowing or talking more honestly about things than the men. I guess there was not as much pressure to put on a front as with the guys. Kathy is 26, with three kids from another marriage, when she fell in love with the 19-year-old outlaw Benny. She lives further west on the west side of Chicago than most people realize is possible, in the neighborhood she lived in as a child.

|

|

Johnny has been president of the Chicago Outlaws for the past eight years. He is a transit truck driver and lives in a comfortable home on the west side of Chicago with his wife Gloria and their two daughters. The problem of funerals that he speaks of here is very real. During the last season I spent around bike riders, I knew, or knew of, five young people who were killed. One was a suicide, two died in cars, one died on his bike (actually he fell off his bike at a slow speed and was run over by a car) and one died drag racing. Inevitably, motorcycle funerals (motorcycles follow the hearse and sometimes the deceased is buried in the club colors) shows a great deal of tension. Often the parents and family of the deceased hated motorcycles, and now blame their loss on the bike riders. I have seen a mourning grandmother walk past mourning bike riders and call them "filthy pigs." The scene brings memories of Romeo and Juliet, with the family in civilian clothes and bike riders in leather staring hate at each other over a loved one's coffin. Cal, or Cal from So. Cal as he is properly called, is 29 and was a Hell's Angel for six years. I first met him at the Outlaws New Year's Eve party in Milwaukee (the party was considered somewhat of an occasion because 100 Outlaws from different clubs in five states managed to get through the night without anyone being seriously injured), shortly after he joined the Chicago club which, Cal says, is the only one he'd consider joining after being an Angel for so long. Cal feels a real sense of change in the membership of outlaw clubs and in the H.A.'s, differentiating between the "old people" (his brother is an active H.A. in the Berdo chapter) and the new punks. |

|

A great change in the motorcycle world began in the early sixties with the introduction of the Honda to the American market. What Honda did was create an entirely new market, and with it came a new motorcycle world, larger and quite different from the old world of the bike rider. Hondas were good to ride around the campus and down Madison Avenue. They had push-button starters. It made motorcycling almost respectable, and now suburbanites wanted a 90cc Japanese bike to keep in the garage between their two cars. (Engine size of the HarleyDavidson CH, the most popular bike with outlaws is 900cc, or ten times as large.) Motorcycle sales doubled, and by 1966, there were 1,250,000 registered in the country. Outlaws don't have much use for the small Japanese bikes or for the people that ride them, but still the current motorcycle boom has greatly affected their world. A much broader base now existed for public interest in motorcycles, and the communications media, which has never been unaware that bike gang stories sell papers, eagerly reported anything outlaw clubs did.

A Saturday Evening Post cover story on the Hell's Angels in 1965 awakened any local newsmen not yet unaware of it, that they too might be able to find a local outlaw club with which to threaten their community. By 1966 it was hard for the Chicago Outlaws to go on a run anywhere without an entourage of TV cameras. The Outlaws themselves are not uncooperative with the news media, often carrying clippings about themselves or their clubs inside their black leather jackets.

Although the Chicago Outlaws and the Hell's Angels originated in the early fifties, most of the new clubs were formed after 1965, and many will tell you they got the idea from a magazine. (The early history of the Chicago club is obscure, although some people believe there was a connection to the old McCook Outlaws, a club that disbanded in 1947 when most of its members became Chicago policemen.) Not unaffected by all the new attention, the Chicago Outlaws in 1966 became, of all things, an expansionist force. Already the largest club in Chicago with its 50-odd members, under Johnny Davis' direction, the club began to organize new clubs under the Outlaw patch. Thus the Milwaukee Outlaws, the Louisville Outlaws and Dayton, Columbus, So. Indiana and Grand Rapids Outlaws. There was even talk of going into Canada. The Milwaukee Outlaws, which unlike the Chicago club cooperated eagerly with the press, became so popular that the Governor of Wisconsin went on TV and promised to clean up the state. Zipco and Beast came to Chicago to hide. It was becoming clear that fame was a two-edged sword. |

|

|

The Cedarsburg Run, one of seven runs the Outlaws made last summer, was a typical example of what has happened now that outlaws are press-worthy. It was held in Wisconsin, and almost 200 bikes came from brother clubs as far off as Columbus, Ohio. The pack had police escorts everywhere it went, the race was canceled, and special radio bulletins announced our movements. Eventually, we all ended up in a lovely state park which the police, armed with riot guns, sealed off. Hundreds of tourists and college kids lined the highway, and with the police and press stationed at about the orchestra pit, the big bad outlaws — Zipco, Sonny, Maddog, Beast, Pig & Co. — proceeded to give them the show they had come for. Without this SRO audience of public, police and press, it would have been an entirely different scene. What does it mean when Angels become movie stars and Cal from So. Cal is the hero of a book? It is in the nature of many things in the bike world, and in any world, to perform and expire for the watching eye of the TV camera. What was once a reality lived and discovered becomes a reality created and re-created for the attention it receives. But if the bike rider is destroyed now in order to bring him into your living room, rest assured that as long as Harley-Davidsons are manufactured there will be others, riding unknown and beautiful through Chicago into the streets of Cicero.

Fitted like sleepers together

""Two on a Motorcycle," by Radcliffe Squires, from The Light Under Islands to be published this fall by The University of Michigan Press. |

|

“The poet, the artist, the sleuth — whoever sharpens our perception tends to be antisocial; rarely ‘well-adjusted,’ he cannot go along with currents and trends. A strange bond often exists among antisocial types in their power to see environments as they really are.” The Medium is the Massage |

|

Original format: Twenty-two page booklet, 4-5/8 by 10-7/8 inches. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

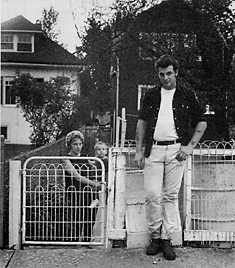

"The Wild One," with Marlon Brando as Johnny, leader of the B.R.M.C. (Black Rebel Motorcycle Club). The eternal popularity of the movie is seen in its constant repetition on television, and to this day it sets the image of the danger lurking in outlaw motorcycle bands.

"The Wild One," with Marlon Brando as Johnny, leader of the B.R.M.C. (Black Rebel Motorcycle Club). The eternal popularity of the movie is seen in its constant repetition on television, and to this day it sets the image of the danger lurking in outlaw motorcycle bands.