| << UbuWeb |

| Aspen no. 10, item 9 |

|

|

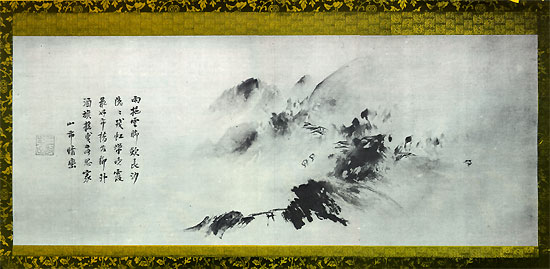

| A Mountain Village In Clearing Mist |

|

|

Ying Yu-chien’s |

detail

|

|||

|

This "spilled-ink" painting (1), is done in the free-spontaneous style of the Ch'an (2) monks of the 11th-century China (southern Sung), which later developed into the Sumiye painting of Japan. Here the philosophy of sudden enlightenment is pictorialized. Just as the sage might see the truth in a flash, so the artist, seized by inspiration, could paint his picture in a matter of minutes. What counted was not hours of laboriously worked-out detail but brief moments of highly concentrated activity. Nothing could be changed once the brush strokes had been put down. The empty spaces were considered as significant as the painted areas — what was left out was as important as what was left in, leaving the viewer to supply the missing detail. The essence of Zen is shown in the swift abstract brush strokes, almost like calligraphy. The poem, an integral part of the painting, translates:

|

|

The following view of Ch'an is from the delightful and authoritative book, "The Chinese on the Art of Painting" by Osvald Siren — recommended reading for everyone: The most concise summing up of the principles of the Ch'an teaching is found in the following words, traditionally ascribed to Bodhi Dharma:

This is the way in which all mystics have spoken, whatever age or school they may have belonged to: Look within yourself; the treasure of wisdom is buried in your own consciousness; if you wish to find it, you must search it out, excavate it by your proper efforts. The teacher can only point out the way, etc. — But in doing this he may use various means and methods, fitting to the age and the surroundings in which he lives. The Ch'an masters were Chinese, imbued with the Chinese mode of thinking and talking, and this may to some extent account for their perplexingly abrupt and paradoxical manner... |

The Ch'an teachers were, evidently far advanced in using words as symbols or blinds; they did it to such an extent that it sometimes is hard to tell whether their intention was to conceal or to communicate their ideas. Their appeal was usually to the student's intuitive faculty rather than to his reasoning mind. A mental shock was considered more valuable than a logical exposition, if it could be administered so that it served to "open the third eye," or to arouse the creative imagination. Naturally such methods appealed in particular to poets and painters to whom the appearances of the objective world were merely symbols of inner realities. As an example of the Ch'an method of interpretation the following stanza may be quoted:

The phenomenal world is filled with mirages of the mind; nothing of it is real; they change and shift as the mind moves. This point of view is graphically illustrated by the following incident from the life of Hui-nêng. The master once came to a place where some monks were arguing on the fluttering of a pennant. One of them said: 'The pennant is an inanimate object and it is the wind that makes it move.' Another said: 'Both wind and pennant are inanimate things and the flapping is an impossibility.' A third monk protested: 'The flapping is due to a certain combination of cause and condition, and a fourth one proposed an explanation in the following words: 'After all, there is no flapping pennant but it is the wind that is moving by itself.' — As the monks could not agree, Hui-nêng interrupted them with the remark: 'It is neither wind nor pennant but your own mind which flaps.' |

|

The reply is most characteristic of the Ch'an attitude, according to which nothing really exists except as a reflection of the mind. The forms and phenomena which we perceive through the activity of the senses or by the discriminations of the intellect have no permanence or existence of their own. They form an ever changing stream of transformations and they would disappear altogether if the ceaseless operations of the reasoning mind and the senses could be stopped. If we want to obtain knowledge about the reality behind the appearances, their essence or 'Suchness,' we must raise ourselves to a state beyond intellection or ordinary thinking in terms of opposites. The thinker must be completely identified with the thought, the perceiver with his object of perception, and ordinary distinctions fade away. It is evident that such a state cannot be described in words which are subject to the reasoning mind, nor conditioned by any terms; it is the state of 'Suchness' which also has been called the 'Great Void.' But it should be distinctly understood that this expression by no means implies nothingness or absence of life. Quite the contrary; it signifies the highest form of reality, the universal aspect of life, a state of existence which contains everything but which cannot be realized by man before he has become self-conscious in the highest part of his being. "When you hear me talk about the void, do not fall into the idea of vacuity," said the Sixth Patriarch, and continued: "It is of the utmost importance that we should not fall into that ideal because when a man sits quietly and keeps his mind blank, he would be abiding in a state of the 'voidness of indifference.' The illimitable void of the Universe is capable of holding myriads of things.... Space takes in all these and so does the voidness of our nature. We say that Essence of Mind is great, because it embraces all things, since all things are within our nature"... |

When fully developed as in the compositions of the Ch'an painters, where the forms often are reduced to a minimum in proportion to the surrounding emptiness, the enveloping space becomes like an echo or a reflection of the Great Void, which is the very essence of the painter's intuitive mind... The word intuition is here evidently used as a designation for man's highest faculty of perception, a kind of spiritual illumination which manifests only when the thoughts and sense-impressions of personal life have been brought into silence. It is the deepest form of meditation... It is the mysterious event which is called wu or k'ai wu (to become, to apprehend) in Chinese, and satori in Japanese, and which is the very aim of all Ch'an training. According to Suzuki, it means "the unfolding of a new world, hitherto unperceived in the confusion of a dualistically trained mind," — a personal experience by which the whole outlook of life is changed... It may well be admitted that these men too were subject to illusions and deceptive impulses, but whatever conclusions they arrived at, they did not hesitate to apply them in their own lives, to transform them into actions and thus to find out their value.... They knew that life is a movement that never ceases, a stream which flows on, whether we wish it or not. They realized that the only way of converting into full value what life has in store for us is by living completely in the present moment, by grasping it by the wings as it flies and not after it has flown. For those who know how to do this, time becomes an illusion; one sudden experience which penetrates deep into the consciousness may become of greater value than years of intellectual study, one apparently trivial incident may open the spring of a hidden source. |

|

But how can such things be made in words or visual shapes? In poetry, perhaps, when it is no longer descriptive but retains an echo of the thing behind the words; in painting which is not imitative but a spontaneous expression for the creative vision. In order to be true and alive these things must be done on the spur of the moment, before the light has faded or the 'spirit-resonance' has died away. It is evident that no kind of painting could be better fitted for such expressions that the Indian inkwork which by its very nature requires the greatest spontaneity in the handling of the means of expression. It must be done quickly and irretrievably, as the paper soaks up the ink; every stroke of the brush must be definite, no subsequent corrections or alterations are possible. As is well-known, this required the most careful and assiduous training, psychological as well as technical, because the brush-strokes became reflections from the mind transmitted by the skill of the hand. Indian ink-painting in its purest form became thus a kind of Ch'an practice, an example of what the 'direct method' of Ch'an meant when applied to art. The painting on the scroll is only a projection of the one which exists in the master's mind, a record of the thing that flashed across the mirror of his soul. It may have been provoked by an incident or an object, but it is no longer the event or the shape that counts, but its repercussion, the indelible traces that it left on the mind. The thing itself becomes a vibration of life; how much it conveys or expresses will depend on the sensitiveness of the receiver and the immediate response of the transmitting instruments. No painter who did not possess a full command of the technical means could ever transmit such fleeting glimpses or momentary reflections from a realm beyond sensual perception. The brush had to respond instantaneously and unremittingly to the pulse-beat of the creative soul; the material labour had to be reduced to a minimum... |

The works of the Ch'an painters might often seem lightly done, thrown down without the least exertion, but the suddenness of the execution would certainly not have been possible if the masters had not passed through a long and assiduous training. It was like the sudden enlightenment, the k'ai wu or satori, which comes on the spur of the moment, when the mind has been cleansed of all beclouding thoughts and attuned to the silent music that accompanies every manifestation of life. The painters called this ch'i yün, the 'spirit-resonance,' or the reverberation of 'the Universal Mind'; they listened to it in the innermost recesses of their own consciousness as well as in every phenomenon of nature: Mountains and brooks, winds and waves, flowers and falling leaves, all revealed to them a reflection or an echo of the 'Universal Mind.' We may call this poetry, or pantheistic romanticism, but to these painters it was actual life and reality. The things that they did, grew out of their own souls; they were part of their own life and character. It was no longer of importance what they represented, whether it was large or small, a whole landscape or only some fruits or flowers, if only it served to transmit some glimpse from a world beyond material limits of time and space like the enlightened mind of the creative master. |

||

|

1. Now in the collection of Mrs. A. Yoshikawa, Tokyo. 2. The word Ch'an is an abbreviation of Ch'anna, the Chinese word for dhyana, a Sanscrit term usually translated as contemplation or meditation. 3. "Chinese Art" by W. Speiser, R. Goepper, and J. Fribourg, trans. Diana Imber; Universe Books, New York, 1964. Vol. 3. © Aspen No. 10, Section 9 |

|

Original format: Single sheet printed on both sides, 18 1/2 by 9 inches, folded in half. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|