| << UbuWeb |

| Aspen no. 10, item 8 |

|

|

| The Idea In the Brush and the Brush In the Idea |

|

|

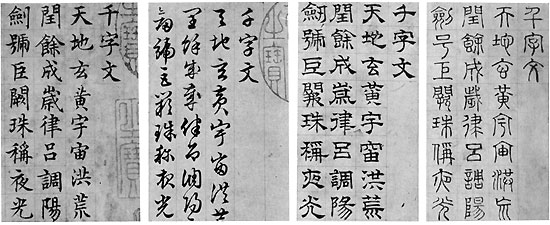

The Ten Thousand Character Essay By Wen Ching-ming (1470-1559, Ming Dynasty) Calligraphy in handscroll form (detail), in ink on paper, in four sections, each 11 in. high and resepctively 20-15/16 in., 20-7/8 in. long. |

""The Ten Thousand Character Essay," composed during the Liang Dynasty (502-549), uses one thousand different characters, each only once. Chinese children memorize it in an aid to remembering the characters, and calligraphers are fond of copying it to show their virtuosity. Here, Wen Ching-ming has copied it in the four main styles of calligraphy: Standard (k'ai), Draft (ts'ao), Clerical (li), and Seal (chüan) in that order. It is interesting to compare the variations in the four styles — and to admire the calligrapher's superb control of the brush in each. |

|||

|

All calligraphy reproduced from the Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan, Republic of China. |

The Idea In the Brush and the Brush In the Idea Calligraphy not only was the most important art to the ancient Chinese, it was the chief and most fundamental branch of every art. To the connoisseur, the contemplation of a beautifully executed piece of calligraphy is the most delectable of pleasures. The calligraphy of a great master is not a symmetrical arrangement of conventional shapes but an adventure in movement similar to a beautiful dance. A favorite story of scholars is how the calligraphy of Chang Hsu of the Yang period greatly improved after he had watched Lady Kung-sun perform the dance of the two-edged sword. Another master, Wen Yung, found new inspiration after watching two snakes fighting. Huia-su (whose work is reproduced on the reverse side) realized new varieties of form while watching wind-blown clouds. The essence of beauty in calligraphy is movement — the brush strokes stretch and sweep, crouch and spring, ink tones swell and diminish, shapes expand and contract. "Line after line should have a way of giving life, character after character should seek for life-movement," an anonymous calligrapher once wrote. The Chinese themselves have developed an extraordinary number of similes to describe this life-movement. A piece of writing is described as "light as floating gossamer," "violent as an attack of wild beasts," "the breaking of ice in a crystal jar," or "raging flames sweeping over the prairie." Teachers deliberately foster such imagery to vitalize their students' work. One noted calligrapher, Chang Yen-yuan, described the seven basic strokes, or the "Seven Mysteries," in these poetic terms:

The quality of the strokes is also judged by whether they have bone, flesh, muscle and blood. These descriptions all derive from nature as does all the art of China. Every tiny stroke of a piece of calligraphy has the energy of a living thing. Every stroke after it has fallen from the brush, must lie on the paper without correction; touching up would destroy its life. There is a saying that a stroke should be started with a force great enough to move a mountain and end with some of it still left. |

|

|

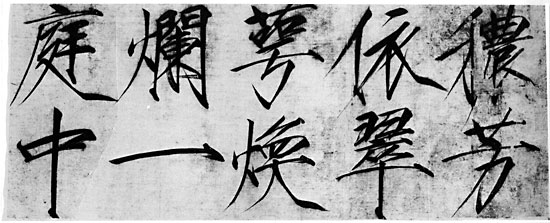

Poem By the Sung Emperor Hui-tsung (reigned 1101-1125) Calligraphy in handscroll form (detail) in ink on silk, 10 1/2 in. by 104 1/4 in. |

Under the aesthetic patronage of Emperor Hui-tsung, the arts flourished in China, with the emperor himself becoming a master at calligraphy and painting, particularly of exquisite, detailed paintings of birds and flowers. In calligraphy, he developed an elegant script style known as "slender gold." This highly mannered but very beautiful style has many reedy strokes similar to those used in flower painting. The scholarly emperor's reign ended in tragedy when he was taken prisoner by the barbarians of the Steppes. He died in exile in Manchuria. |

|

The speed of the stroke is another important factor — every stroke is composed of alternating quick and slow movements. As Li Ssu, in what is attributed to be the earliest writing on technique, described the correct use of the brush: "Give it a quick turn first and then bring it down swiftly like a hawk after a bird. Let it proceed naturally and do not work it over. The advance of the brush is as free as a swimming fish in water, and the swing of it, as rising clouds over a great mountain." As he indicates, the beauty is of plastic movement, not of designed and motionless space. Each character should have a stable stance with a gesture of movement and the center of gravity falls upon the base. One side may be larger or denser but the whole still must not overbalance. An asymmetrical balance is sought since it possesses more movement. This is achieved by the imaginary plotting of the character upon a nine-fold square, invented by some ingenious writer of the Yang dynasty. If the square were divided in half or in fours, the result would be symmetrical, but the nine-fold square permits balanced asymmetry. The writer not only plans his strokes but also his "arrangement of spaces," which is a vital consideration in the Chinese philosophy of art. A great variation in individual styles is thus possible. The pursuit of calligraphy is a lifetime undertaking and the majority of the famous calligraphers reached the height of their powers only at a venerable age — and after a lifetime of unremitting commitment and obsessive practice. No matter how long they practiced, they never seemed satisfied with their work. The finishing of one piece was only the beginning of the next. There are many stories describing calligraphers' addiction to their art — Chang Chih who practiced outdoors left the water of a pool black with ink; Chung Yu after a ten-year withdrawal to the mountains left the trees and rocks covered with ink; Chih-Yung left five large baskets filled with worn-out brushes after 40 years of daily practice. |

|

|

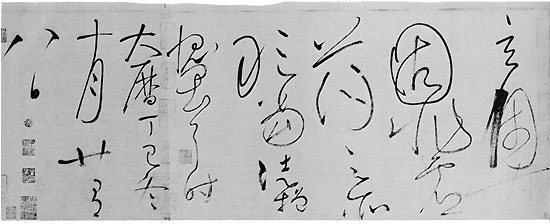

Autobiographical Essay By the Monk Huai-su (dated 777, T'ang Dynasty) Calligraphy in handscroll form (detail), in ink on paper, 11-3/16 in. by 295-5/8 in.. |

In contrast to the elegance of the Emporer Hui-tsung's calligraphy is this rare example of the "wild" Draft script (K'uang-ts'ao) by the Buddhist Monk Huai-su. Composed with great freedom and fervor, the characters suggest "both the untrammeled nature of the writer and the state of drunkenness he was probably in when he wrote," as one critic observed. Huai-su himself termed it "the calligraphy of an intoxicated immortal." Being very poor and addicted to calligraphy, he planted banana trees and harvested their broad leaves for writing paper. He is also reported to have left his mark wherever he went, exuberantly applying his brush "to the walls of temples and hamlets and even to clothes and household pots and pans." |

|

Calligraphy is looked upon as a healthy exercise since it involves the whole body. It is practiced in the morning when the body — and the world — is fresh. Usually, a calligrapher writes standing at a long high table or stand, but when writing a large piece he puts the paper on the floor. Next to the paper are arranged the "Four Treasures of the Room of Literature," the brush, brush-stand, ink and inkstone. The brush is made of animal hair — sheep, deer, fox, wolf, mouse or rabbit — tied in small bunches to a hollow reed or bamboo. The ink is not liquid, but soot of burnt pinewood or of lamp black mixed with gum, warmed and left to solidify. It is moulded into small sticks often decorated with carved designs which make them small pieces of art in themselves. When ready to write, the calligrapher grinds the ink stick with a little water upon the ink-stone — grinding with his left hand to leave the right rested for writing. As he grinds, he meditates, making his mind as calm as possible. An early description of the calligraphic ideal is given by Ch'en Ssu as having been written by Ts'ai Yung (133-92): "In writing, first release your thoughts and give yourself up to feeling; let your nature do whatever it pleases. Then start to write. If pressed in any way, even if one had a brush of hair from hares of Chung-shan, one would not do well. "In writing, first sit silently, quiet your mind and let yourself be free. Do not speak, do not breathe fully, rest reverently, feeling as if you were before a most respected person. Then all will be well. "In its forms, writing should have images like sitting, walking, flying, moving, going, coming; lying down, rising, sorrowful, joyous; like worms eating leaves, like sharp swords and spears, strong bow and hard arrow; like water and fire, mist and cloud, sun and moon, all freely shown — this can be called calligraphy." To be appreciated on another level are the seals which adorn (hopefully) and. sometimes disfigure Chinese and Japanese paintings. Each is the "signature" of an owner. Thus the history of a painting can be traced through the seals which have been impressed on the painting as it passed from owner to owner through the centuries. The owners most appreciative of aesthetics placed their seals where they would least detract from the art while other owners revealed amazing egoism by choosing the most prominent positions for their seals — CHING YING Sources: ""Chinese Calligraphy" by Chiang Yee (Methuen & Co. Ltd.) ""Chinese Calligraphy" by Lucy Driscoll and Kenji Toda (University of Chicago Press). ""Masterpieces of Chinese Calligraphy in the National Palace Museum (National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan). ©Aspen No. 10, Section 8 |

|

Original Format: Single sheet printed on both sides, 33 3/4 by 6 inches, folded into thirds. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|