| << UbuWeb |

| Aspen no. 1, item 4 |

|

|

| Ski Roaming |

|

Ski-roaming,

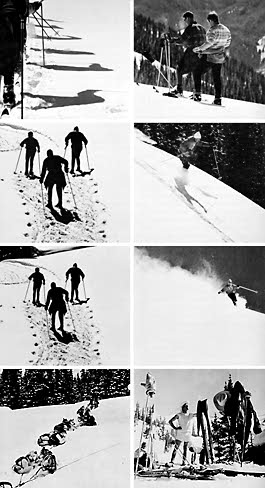

lift-shunning, by Denis Higgins and John Henry Auran It's like hiking, only with skis on. Its appeal is to the dedicated purists, the anti-social swingers, the mavericks who eschew the companionship of the long string of bored enthusiasts at the bottom of the ski lift, to return to the mode of the fathers. We refer, of course, to that growing group of hardy primitives who seek in the unpeopled passes and icy highlands the isolation of the long-distance skier. Sure, they're perverse. Now that the ski entrepreneurs have spent millions manicuring the slopes and planting ski lifts up every available mountain, the crosscountry skier has decided he'd rather set a course of his own. And more often than not, the course is uphill, the conditions unpredictable. In a world where one expects to find an empty beer can on Everest, the sight of smooth and untrammeled stretches of shining snow is increasingly rare. It takes more effort and time to climb the heights and see what the pioneers saw, but there are few sights to equal it. |

|

There have been few refinements in the sport since the 1880's when crosscountry skiing was Aspen's sole method of transportation at times. Those were the days when a man skied the 70 miles from Aspen to Leadville in one day, setting a record that still stands. And the days when the transplanted Norwegian and Swedish miners of the Little Annie Mine exchanged picks for poles and skied in the basin after work just for the sport and the hell of it. Modern times have brought a few innovations to ease some of the drudgery out of it. Mechanical transports will get the cross-countryman away from the people and up to the high country. Instead of doing a pioneer-style herringbone up to the starting point, today's adventurer has the choice of helicopters, snowcats, jeeps, and even teams of yapping and authentic Huskies. But the hardy connoisseur still prefers to pack in on snowshoes, skis strapped to back, relishing the slow trudge to the highlands. The cross-country haul is not for the habitue of the boutique. The equipment must be simple, rugged, and lightweight. Oxygen is energy, and there just isn't that much oxygen up there. Part of the beauty of lift-shunning is that fashions don't count. Nobody cares if you're wearing an army parka or a belted anorak, so long as it's light and warm enough to keep you moving. In fact, the touring buffs, shun sartorial competition, and late in the season, it's not uncommon to see skiers scraping across a high meadow in various stages of déshabillé as they shed their clothes in the high noon of the spring sun. |

|

|

The few skiers you do meet on a crosscountry traverse usually are of five different breeds: There is the cross-country racer. A grim and serious type whose skiing life is dedicated to lopping off a few seconds from his previous time over such forbidding distances as 15, 30, 50 kilometers. He is occasionally seen in Aspen, seemingly defying all natural laws by going against the stream of traffic on Aspen Mountain. Then there are the tourers, the philosophers of the ski-trail, poured in the mold of John Muir. Somebody has said, when you ride up a mountain on a lift you think, isn't it pretty and promptly forget it. But a tourer never forgets. He has been on and in the mountain, not over it; he has rattled over the rocks and rested under the trees. He never forgets. To him each mountain is a different skiing world, and his "must" equipment is a sleeping bag and rucksack of supplies so he can do without the conveniences of civilization for days on end. |

To the tourer, nature is the cake. The fast and short and occasional downhill run, the frosting. Then the powder hound. He doesn't care about the scenery or the physical challenge of the cross-country run. What he wants is snow— virginal, freshly fallen, untouched by man and preferably untracked by so much as a rabbit. Give the powder hound a long, sloping meadow of this and he will herringbone up Little Annie Basin backwards to get to it. Then there's the ski-nut. The fanatic. A combination of all three preceding types. He loves the cold, the danger of a lonely cross-country run with all its stumps, crevasses and hidden rocks. He revels in the scenic beauty of the high country, particularly when he can view it moving at high speed down deep powder. The ski-nut is easily distinguished from _is fellow nonlift skiers by the sheer tonnage of equipment he owns and his frequent references to his "rock skis." |

|

Then there are the rest of us, the bumbling sometime skiers, who can't handle crust, soggy snow. or even deep powder who are absolutely exhausted after five minutes of uphill trudging— let alone five miles of it— but who can't resist the challenge of a trip to the roof of the world. The scenic beauty, the satisfaction of being self-sustaining in diffcult country, the adventure, and the physical effort involved, all combine to make ski-roaming irresistible to us— and suddenly we find ourselves babbling about this, "the purest form of skiing." One of us should be included on every touring party. We become the court jester, provide the comic relief that turns even the grim moments into slapstick. And as we pant to a halt, we give all the stalwarts an excuse to stop and surreptitiously catch their own breath. And probably we love it more than any of the others. The ski-nut is virtually a year-round phenomenon at Aspen, for the determined ones can almost always find a spot on which to exercise their skis "in the back of Aspen." When the snow corns up in midApril— just about when the lifts close— until early June or July, you can spot jeep parties of them bumping their way up Ashcroft road to the snowline, then working their way on skis to the snowfields of their choice. |

The tourers are there in full force too, adventuring into Montezuma and Pearl Basins, Mt. Hayden, into the Snowmass Wilderness and Taylor Pass, over to Cooper, Star and Italian Basins, bedding down at night in the Tagert and Lindley Memorial Huts or Stuart Mace's chalet which serves as his Huskie trip headquarters. Summer playground for the ski-nut is vast and rugged Montezuma Basin. Those prepared for a jouncy jeep trip can ski there in the July sun on a snowfield "big enough for a good slalom run." The ski-nut makes his winter debut at Independence Pass. Closed throughout the winter, it is the place to go before the lifts open and after they close. Come October, as many as a hundred skiers from as far away as California somehow know when a cap of snow appears on the pass. Almost as if by magic, cars prickly with skis find their way to the 12,000-foot level and slalom poles spring up on a small snowfield to the west of the pass. In spring, as the snowplows work their way to the top, they are followed by a small army of skiers, intent on getting in a few more runs on deep, but somewhat soggy snow with a minimum of climbing. But whatever the type, and wherever the snowfield, the non-lift skier enjoys a sport that has as much in common to the clean shaven mountain variety of skiing as motor-boating to sailing. Long-distance, crosscountry skiing can be dangerous and exhausting and not much downhill. Gravity is the enemy, not the skier's friend. But ask a tourer of a powder hound or a ski-nut coming dead tired off the trail, and he'll tell you that's just the way he wants it. |

|

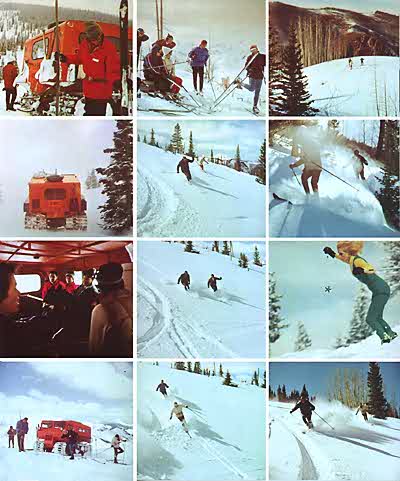

For the ultimate ease in lift-shunning, Snowmass skiers board ten-passenger snowcats which lumber up the mountains like some red monster left over from the Ice Age. With the whole world spread out below, you start down, carving your own trail through deep powder, soft as a featherbed to fall in and just as hard to get out of. Once you've gotten past the first frightened, floundering moments of off-trail, deep-powder skiing, it's the nearest thing to flying. Slalom through the spruce. Herringbone up a hill. Negotiate a fence. Swoop and float your way to the bottom. When you get there, the only thing you want to do is go right back up again. |

|

|

Original format: 12-page booklet, 9 inches by 12 inches (4 pages 9 inches by 6-1/2 inches). Three pages in color. Photo credits: Ray Atkeson, Bob Chamberlain, Joern Gerdts, Horn/Griner, Milmoe, Loey Ringquist. Numerous photos are omitted here to reduce download time. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|