| << UbuWeb |

| Aspen no. 1, item 5 |

|

|

| The Benedict House |

|

|

by Peggy Clifford |

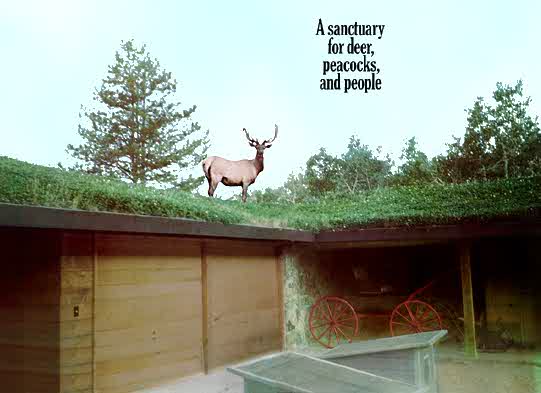

An elk grazing peacefully on the sod roof at Stillwater Ranch one morning was a bit of a shock—but it also was indisputable testimony that the architect had proven his theory: "Good architecture can only complement nature and need not destroy it." The house admirably lives up to the challenge, possibly because it was designed by the architect strictly for himself and his family. It's the home of Fredric and Fabienne Benedict, their four children, and a profusion of pets—a magnificent Belgian sheepdog, a comical Great Pyrenees, ten ducks, four finches, a peacock, two kittens, four horses, and a pony. A conservationist concerned about the destruction of the natural landscape by haphazard urban sprawl, Benedict planned his house to intrude as little as possible on the beauty of the site—an aspen-covered knoll sloping down to a trout stream, deep in a 150-acre oasis just outside Aspen's town line. Rimmed by the surging Roaring Fork River, it has rolling meadows punctuated by thick stands of aspen trees, a small lake, and mountains on every horizon. It's an incredibly beautiful natural setting for a uniquely natural house. |

|

|

The grass and clover roof — green and luxuriant in summer, white as a snowbank in winter — glistens in the sun as the family sets out for a ride, by carriage or by sleigh, depending on the season. |

Low and lean-lined, the house settles totally into the landscape. The sod roof—equipped with its own sprinkler system which fills the air with watery rainbows—literally extends the natural ground cover. In places, the roof actually joins the hillside to create an organic unity which Frank Lloyd Wright, Benedict's mentor, would approve. The rambling floor plan conforms so completely to the contour of the site that there is no one spot from which the entire house can be seen. To further unify the house with the land, a waterfall pours off the roof into a rock-ringed pool. The water then flows in a stone trough around the house—a sophisticated irrigation ditch which cools the air in summer, waters the gardens, and ultimately irrigates the horse pasture. Nature is at home inside, too, in a two-story conservatory with a glass roof, stone walls, and a capricious fountain. The Benedicts are gardening enthusiasts who have risen to the greenthumb challenge of a short growing season at an 8,000-foot altitude. Thus, the tropical garden is an essential part of the house, sunk into the ground on the theory that the heat absorbed from the winter sun by day helps carry the load at night. It is lush and green year-round and, depending on the strange calendar of the plants, filled at times with incredible color. More than 50 kinds of flowers flourish there—camellias, jasmine, bougainvillea, orchids, angel's trumpet, passion flowers, orange trees. On one side, a deck is suspended above the foliage, like a child's tree house in a strange and beautiful wonderland. |

Aspen trees sprout through the floor, the rugged peaks of Independence Pass loom in the distance beyond the airy deck.

The Benedict's peacock gazes imperiously at his realm. |

Beyond the upper story of the conservatory is an outside deck with aspen trees sprouting through the floor. It provides a awesome view of the river and the rugged natural sculptures of Independence Pass, and gives one the sense of sailing up the Rockies. This is the view from the living-dining room also, and is all the more dramatic because it is not seen as you approach the house, but is revealed only after you are inside. The house is planned for such visual surprises. The ranch road winds through shimmering aspen groves and then, unexpectedly, there is the house. The front door, at the end of a short tunnel-like hall through the ground, opens into the opulence of the conservatory bursting with flowers; stone steps lead you through this lushness into a cozy, comfortable living area where the river view is suddenly revealed. When approaching from the rear entry—which is more frequently used, in good country tradition—you arrive at a parking court which is set into the ground to give a sense of shelter and to screen the river view until you are in the house. The living, dining and kitchen areas overlook the conservatory and are designed as one large room, reminiscent of a country kitchen. Although as functional as a can-opener, the kitchen is almost an ornament. The refrigerator is hidden behind a wooden wall and a waist-high brick wall wraps around the stove. Cupboards and decks are mellow wood. Most of the walls and lodge pole ceilings are painted white. Other walls and fireplaces are natural stone found on the site. Floors are brick. Color and contrast are provided by the vivid reds and pinks in the upholstery and the objects d'art which are everywhere, ranging from baroque carvings to pre-Columbia pottery to antique kitchen utensils. There are, in fact, many more "things" than pictures hanging on the walls. Victorian doors, collected in the area by the Benedicts, with colored glass panels and ornate carving, add a sense of irony. Much of the furniture is primitive early 18th century, some of which was found in Europe by Mrs. Benedict. When they were married, Benedict had no interest in antiques, while Mrs. Benedict was a seasoned aficionada. Now he says that he has been "educated" by his wife and has a tremendous "appreciation and respect" for old things. Believing one can happily blend the old and the new, he often uses old glass and railings in utterly contemporary buildings. |

These beautiful round wooden faces of the moon and the sun were found in France by Mrs. Benedict's mother, poetess Mina Loy. |

The children's wing—with large playroom, small kitchen, bathroom, and two bedrooms—is organized, neat, and practically arranged to survive the tumult of four children, their friends and pets. Here, the housekeeper and younger children sleep. Originally, the Benedicts planned to have all the children sleep in the wing, but this "sensible" plan was abandoned when they found it terribly lonely in the main wing by themselves. With Aspen's long snow of a winter, the wide roof overhangs not only provide a visually pleasing sense of shelter, but also give protection against snow and rain in moving from one area to another. In the dead of winter, you can feed the peacock in bedroom slippers. In summer, the wide overhangs serve as an umbrella to keep the house cool. Long before he began designing his house, Benedict had decided to use a sod roof because he felt it would make the "most organic kind of house." As it was his own house, he was free to try a number of other experiments. Several enabled him to use a variety of materials native to the Aspen area which were not only appropriate and pleasing to the eye, but practical in this climate. A "prefabricated" system was developed, using relatively inexpensive solid timbers of native Engleman spruce for the outside walls—planed on the inside, rough-sawn on the outside. Spruce mullions, jambs, and sills were milled to fit into the walls. The result: a house of surprisingly few component parts, a house in the tradition of the log cabin, but done in a modern way. The exterior is unfinished and slowly weathering to the rich brown characteristic of high mountains. A second experiment proved that inexpensive, native materials could be combined to make a striking, handsome house, while the money saved on materials could be invested in highly skilled carpenters and masons. Pine poles for the ceiling were picked up free from a ski trail being cleared. Granite stone for the walls came from the building site itself during excavation. Bricks for the floor came out of an abandoned mine. Spruce timber for walls, window and door frames, and trim was bought from a small local mill at $70 per 1,000 feet. The house was built by the best masons and carpenters Benedict could find. The result was a beautiful and original house which has become a landmark in its own time. |

Interior deck seems suspended above the conservatory foliage like a tree house. Bright pinks and purples of the upholstery echo brilliant colors of the flowers. |

The house is no more unique than its owners. One of Aspen's first modern pioneers, Fritz Benedict is a tall, handsome, agile man with a modest voice, a relaxed manner, and a quiet singlemindedness. A native of Medford, Wisconsin, he first came across the remote little town of Aspen during World War II when he was stationed at nearby Camp Hale with the famed 10th Mountain Division. While serving with the division in Italy he kept thinking about Aspen and when he returned to this country in 1945, he sped straight back to Aspen and sold his car to make a deposit on a 1,000-acre ranch on Red Mountain, north of town. In those days, there was only one other house, an empty relic from the mining heyday, on the mountain. A rough trail wound down to town. His first years in Aspen were colorful and chaotic. He had studied architecture with Wright for three years before the war, but in 1946 there was little work for an architect in Aspen, so he tried a variety of vocations. He ran a dudeless dude ranch. He raised pigs. One summer Richard Dyer-Bennett took over the ranch for his music school which climaxed its season in comic disaster when the ill-fed pigs attacked the students. In 1948, Benedict sold the first piece of his ranch and designed and built a house for the new owners. That was the beginning of the development of Red Mountain, which has since become Aspen's most prestigious residential area. Since then, Benedict as much as anyone, has shaped the look of contemporary Aspen. His mark is everywhere—in the twentyfive lodges and business buildings he has designed; the five residential areas he's developed; the Aspen Meadows and Seminar Building on which he collaborated with Herbert Bayer, a Bauhaus leader; the new campus for the Aspen Music School. Nobody knows how many houses he's designed. A member of Aspen's zoning boards for years, he has helped develop a stringent code which, among other things, has barred neon signs and billboards. As interested in conservation and planning as in architecture, he is an exponent of the new concepts of density zoning. In this approach to land use, buildings are arranged compactly in certain areas, while meadowlands, stream banks and the like are dedicated to non-use. Thus, urban sprawl is minimized and beautiful natural areas are preserved for the enjoyment of everyone. "The entire country has an increasingly metropolitan character," Benedict notes. "There is no longer any definition between city and country. Urban sprawl is spreading everywhere in the U.S., while in Europe, the towns and villages are compactly arranged and the country remains green and unscarred. I have become much more interested in designing villages than individual houses or buildings." At one time, Frank Lloyd Wright designed a mythical city— Broadacre City—in which every resident had a minimum of one acre of property. Actually, many visionaries dreamed at one point of lots of land for each family to enjoy exclusively. While admiring their aims, Benedict feels this concept is no longer possible since it "uses up land too fast." He believes that the same end—air and green space for all—can be much more completely achieved with cluster planning. "It doesn't matter that your neighbor is 25 feet away, if you can look out on a vast rolling meadow," Benedict says. "We have to stop wasting land. We have to preserve the countryside." At the moment, Benedict, in collaboration with Edward Beall, director of planning for the Janss Corporation, is busy planning and designing the first of eight villages in the gigantic Snowmassat-Aspen area. Eight miles west of Aspen, encompassing 3,300 acres of private land and 6,200 acres of National Forest land, Snowmass is being developed carefully and thoughtfully to intrude as little as possible on the landscape. "We're not trying to devour the land at Snowmass, but to use it intelligently," Benedict says, pointing out that the first village will cover only about eight acres although it will accommodate about 600 people in 15 different hotels. There will be underground parking and only pedestrian traffic in the streets. |

A man-made waterfall cascades off the roof into a pond where ducks conspire. |

Each building will have a look and flavor of its own, but all will harmonize with each other. "Harmony without monotony," Benedict says, "is my idea of what architecture should be... harmony with the natural surroundings, harmony with the adjacent buildings, harmony within itself." The buildings will be of pre-stressed concrete, but Benedict is trying to avoid a boxy, cubistic look. "We are working for a pleasing play of volumes. We plan to have the buildings pyramid toward the center of the cluster to avoid a squared-off urban look. We will use lots of wood on the exteriors for a warm, rural look." Denying that he has consciously aimed at developing a Rocky Mountain style of architecture, he admits his preference for warm, textured materials in this cold climate, and feels he can avoid the normal "industrial, antiseptic look" of concrete by texturing it and by artfully arranging the masses in an organic way If Benedict is excited about Snowmass and the opportunity for proving his theories about intelligent land use, he is also enthusiastic about another project, called Roaring Fork Inventory, in which he's involved along with Robert W. Craig, a former Institute official and Woody Creek rancher, and Jack Snobble, of the Colorado Rocky Mountain School at Carbondale. In conjunction with state and federal agencies, they are cataloging the resources of the Roaring Fork, Crystal, and Frying Pan River drainage systems and planning ways to save these unusual natural resources from misuse and destruction. |

The peacock shares a French-inspired vegetable garden with the ducks.

Deck and conservatory are all the approaching visitor sees from the front. |

As Benedict put it, "When a highway department decides to build a highway, they just proceed with their plans without consulting anyone. This often leads to ugly scars on the' landscape. We feel that everyone—residents, state and federal agencies—must work together to save the countryside." 1948 marked the beginning of Benedict's architectural impact on Aspen; it was also the year Fabienne Lloyd came to Aspen to visit her sister and brother-in-law, Joella and Herbert Bayer. Born in Paris, she was the daughter of Mina Loy, celebrated poetess of the twenties, and Arthur Cravan, proto-Dadaist and nephew of Oscar Wilde. Her father once boxed four rounds with heavyweight champion Jack Johnson as a Dadaist experiment and had big posters printed announcing the event. Mrs. Benedict has the same puckish enthusiasm for the original and unusual. Fond of intricate practical jokes, aimed principally at deflating the pompous and pretentious, she is totally irreverent one minute and deadly serious the next. Even her friends have trouble separating the serious from the surreal. In Paris, by the time she was 14, she had sold a painting to the Queen of England. Three years later, she was studying at the Art Students League and the Parsons School of Design in New York, developing into a free-lance designer, specializing in packaging and jewelry. Talented and precocious and still in her teens, she could count among her customers Helena Rubinstein, Lucius Beebe, Shirley Temple, Eddy Duchin, Rosalind Russell. She and Benedict were married in March, 1949, and lived in the brick Victorian house on his ranch until 1952 when they moved into the Bowman Block, a ramshackle building which Benedict was restoring. He still maintains his office there, with a staff of 12, including Mrs. Benedict who describes her office role as "pottering about, feeling martyred and indispensable." In contrast to her husband who is a mountain climber and expert skier with many trophies, Mrs. Benedict is disinterested in most sports. She keeps trying skiing... and giving it up forever. But she enjoys horseback riding with her family. She plainly loves the land, works hard in her gardens and conservatory, and devotes much time to her children and the animals. The stable wing of the house was built because the Benedicts planned to breed horses. However, they found it much too time-consuming and reluctantly gave the project up. The four children—Charlotte, 14, Emilie, 13, Jessie, 9, and Nicolas, 3—are active and enthusiastic, like their parents. Emilie enjoys the concerts at the Aspen Music Festival, likes to cook, and when asked about hobbies, said thoughtfully, "Well, I loved children." Charlotte is the best rider and most interested in the outdoors. Jessie's great interest is dancing, and already is described as "the world's greatest living dancer" by her mother. Nicolas is interested and into everything. The older girls embroider beautifully, make beaded flowers, and paint rocks in fanciful designs. They all have a curious old-fashioned elegance and impeccable manners. With their pond, the river, their horses and plenty of space to roam around in, the Benedicts lead an independent and selfsustained life. The ranch is lovely and serene. The house is original and distinguished. The people are aristocrats in the best sense of the word—attuned to the world, private, possessing style, wit, intelligence, and imagination—sharing their delights with each other and their talents with the community. The atmosphere is comfortable yet cosmopolitan, relaxed yet exhilerating. Indeed, here are the ingredients of the beautiful life. One envies the peacock. |

Brightly colored finches dart about their cage outside the kitchen window.

|

A BENEDICT BUFFET:

Although one of the best cooks in Aspen, Fabie Benedict maintains she hates to cook and her idea of a perfect party is an alfresco luncheon on the terrace. However, a wintry Benedict menu is apt to be this one, cooked entirely the day ahead so the hostess can swoop home from a horseback expedition, the office or whatever and serve supper for twelve—and scarcely enter the kitchen. Mrs. Benedict rarely serves canapes because they "spoil appetites for the real repast." Pot-au-feu Aspen French bread with marrow butter Horseradish sauce Tossed green salad Fruit, cheese, crackers Red Burgundy wine The kitchen is deserted. The guests are in the conservatory. The hostess doesn't stir from the cocktail conversation. The beautiful soup is in the pot. Pot-au-feu isn't quite that easy but looks it. Prepare the day before in five hours time. An hour before serving, put back on stove to heat. Keep piping hot until ready to serve. The steaming broth ladled from a tureen. The meat sliced, chicken in pieces with the vegetables on a great platter. Have everything hot, hot. Platter, plates, et al. With it, a creamed horseradish sauce. To complete the meal, fill the bread basket with crisp hot French or Italian bread, spread inside with marrow butter. A beautiful French mixed green salad. Loose and full with fine tarragon wine vinegar, real French olive oil, coarse salt, and ground fresh pepper, fresh herbs hopefully. Bring on tough Finnish crackers and English water crackers with a dessert cheese, like Danica or a good goat cheese, and fresh fruit. Pears, apples, grapes. A superb red Burgundy wine flowing right through to the end. What more. POT-AU-FEW ASPEN (For 12 hungry people—or adjust the recipe to fit the crowd.) Into the pot, a huge covered kettle, iron or heavy ware, go: 1 T. coarse salt, sprinkled over 1 knuckle of veal, sawed in pieces 8 marrow bones, 2-3 inches long, tied up in a cheesecloth 6 lb. rump beef. Solid meat. No bones. No fat. Tied to hold shape. And these soup vegetables cut up: 4 carrots Several stalks of celery 4 white onions peeled, whole, stuck with a whole clove 2 leeks, if available With a bouquet of herbs, tied in cheesecloth, made up of: 8 peppercorns 4 garlic cloves 4 bay leaves A handful of fresh parsley Pour over it all: 3 cans of beef bouillon 4 cans of clear chicken broth Enough water to cover contents Bring slowly to a boil over medium heat. Stir occasionally, remove gray scum as it rises to the surface. Simmer covered for 2 full hours. If you are making marrow butter (see recipe at end), scoop the marrow out of the bones after pot has simmered only 15 minutes, then return bones to pot. Then add: 1 plump stewing hen, 5-6 lb. whole, trussed Check for taste, add salt. Add more water as needed to keep the level up. Cover and simmer for 1-1/2 or 2 more hours, until meat and chicken are done. Remove meat, chicken. Discard veal and marrow bones, soup vegetables, bouquet of herbs, chicken skin (bones too, if you're feeling energetic). Put meat, chicken back in soup. Refrigerate. Prepare the following vegetables separately. For twelve, allowing 2 of each vegetable per person: 24 carrots, long and skinny, scraped and halved longwise (if parsnips are available, make it half carrots and half parsnips) 24 white onions, peeled, whole 24 leeks, green ends cut off halfway Cook all together briskly in a little salted water until tender. Don't overcook. Cool, refrigerate. On the day of the Pot-au-feu, remove the grease now solid on the top. Reheat slowly. Heat vegetables separately. Keep hot until ready to serve. FRENCH BREAD WITH MARROW BUTTER To make marrow butter for your hot French bread, scoop the marrow out of the bones after pot has simmered only 15 minutes, then return bones to pot. Work marrow into soft butter with grated shallots and spread between 1-1/2-inch slices of long French bread, (don't slice clear through). Wrap bread in foil, leaving the top exposed. Heat in 350-degree oven 'til hot (about 15 minutes). HORSERADISH SAUCE Into the double boiler cooking constantly go: 3 tbs. butter 3 tbs. flour 1 cup Pot-au-feu broth, hot 1/2 cup milk Melt butter, stir in flour until smooth. Then the broth, slowly, and milk. Stir onward. Cook covered for 20 minutes. Strain if not entirely smooth and set aside until just before serving. Reheat in double boiler and add: Salt, pepper, pinch of sugar 1 cup bottled horseradish (few can detect it from the fresh) Serve hot. This sauce also is beautiful with fish. Just substitute fish stock for Pot-au-feu broth and proceed ahead. TOSSED GREEN SALAD The best salad is still the simple, classic French tossed salad, a combination of whatever greens are available that day—Boston, romaine or Bibb lettuce, watercress, young spinach, chicory, endive, even dandelion greens—with a dressing made of three parts olive oil to one part wine vinegar and/or lemon juice, coarse salt, and freshly ground pepper. Coarse salt has the advantage of not wilting the salad, since its coarse crystals do not dissolve on the leaves. A sprinkling of fresh chopped herbs—tarragon, chives, chervil, parsley, lemon balm—is preferred, but if the garden is bare, a pinch of curry or dry mustard added to the dressing will give zest. Serve after the Pot-au-feu to "refresh the palate." |

|

Original format: 14-page booklet, 9 inches by 12 inches, fold-out cover. Photo credit: Ferenc Berko. Floor plan and numerous photos are omitted here to reduce download time. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|