|

Sound Sound UbuWeb UbuWeb |

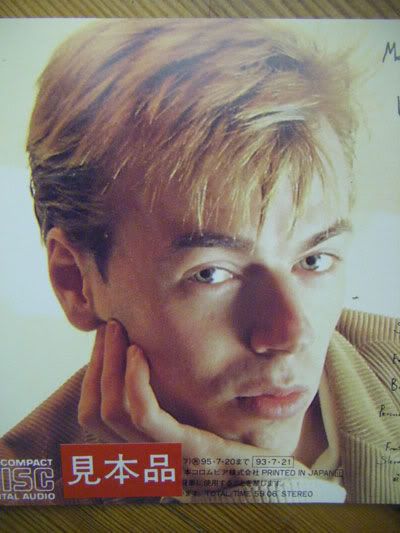

Momus (Nick Currie) (b. 1960) The Poison Boyfriend (1987) 1. Murderers, the Hope of Women: This, and the two tracks that follow, are actually CD extras, the songs that made up my first Creation release, a 12" 45rpm EP. The three songs were recorded as a demo for Blue Mountain Music at the end of 1986, with Julian Standen producing. The first Momus EP, The Beast with 3 Backs, had been "three songs about threesomes". Having done sex, I thought I'd do death ("the last pornographic frontier of the bourgeoisie", as Peter Greenaway called it, promoting his 1985 film A Zed and Two Noughts). The guitar solos in these songs are -- amazingly enough -- played by Lemmy's son, Paul Inder. Murderers, the Hope of Women was inspired by Wedekind / Pabst's Lulu and an expressionist play by Oskar Kokoschka. It basically looks at marriage as if it were an extremely slow motion knife crime. How I rate this now: I think it's a strong song, melodramatic and tragic. It's more impressive than likeable, though. 2. Eleven Executioners: I was reading a history of cabaret, and liked the idea of Die Elf Scharfrichter, Munich's (and Germany's) first cabaret, so this song is a tribute to it. It's a song influenced, also, by Friedrich Hollaender, who wrote the songs for The Blue Angel, sung by Dietrich. (Other Hollaender-influenced songs of mine: Morality is Vanity, Gilda.) The rhythm at the end is a ballgame my mother taught me. The song concludes with, really, the opposite of the moral that "there is nothing to fear but fear itself"; the executioner who most kills our sense of aliveness, in my song, is the one who kills our fear of death. Death is "the black backing the mirror needs to reflect". We should fear it. How I rate this now: The arrangement is a bit scrappy, but it's a fun song. 3. What Will Death Be Like?: Why was a 26 year-old man so obsessed with death? Well, existentialism had been a big formative influence on my teenage years. I was steeped in that. But there was also the fact that death was something you weren't really supposed to dwell on in pop music, which made it "transgressive", and that was something I wanted to be. A difficult artist, a singing author hitting you with big themes. Something like Leo Ferre or -- of course -- Jacques Brel, whose La Mort looms large behind this Wittgensteinian list of things death won't be like, because they're all things pointing towards death, but firmly anchored in life. How I rate this now: Powerful, but rather worthy. Oddly enough, it now sounds to me like a song about ambition, as if it's not about death but about being a great writer. It's bloody difficult to play live (which doesn't stop me trying). 4. The Gatecrasher: This is where The Poison Boyfriend album really starts, and I think the more sensual, better-produced sound really marks it apart from the EP that precedes it. The influence on this song is Tom Waits and Joni Mitchell. I remember telling the session bassist to "play like Jaco Pastorius". The album from this point on is recorded at The Chocolate Factory in New Cross (near where friends like Band of Holy Joy and Test Department were living), in early 1987. It's the record that established me critically, getting raves pretty much everywhere, and making the critics' End of Year lists in the UK music weeklies. How I rate this now: It really sounds like a different artist, an 80s literary singer-songwriter somewhere between Lloyd Cole and Suzanne Vega, or perhaps Martin Stephenson or Stephen Duffy. It's literary and a bit conservative, a bit Q and Mojo friendly (not that they existed at that point). This is my only album produced by someone other than myself, and I remember having totally different ideas for how it should sound. It would have been Casio reggae if I'd had my way! 5. Violets: This reminds me that I was mates with The Tiger Lillies at the time -- later worked with some of them. There was a whole neo-cabaret thing going on in London in the late 80s: The Tiger Lillies, The Band of Holy Joy, the "New Routes Acoustic Music" scene at the Troubadour in Earl's Court, where friends like Preacher Harry Powell and Kevin Wright would play. Everything was poetry and coffee bars, basically. And we all signed on. Anyway, Violets is a vaguely threatening song about terrorism in Italy and Ireland, and there's a subtext (spelled out via the nouns in each verse) about preventing terrorist explosions by giving disgruntled people their own TV stations. There are reflections here of my love for Leonard Cohen, and my relationship at the time with a French girl called Zoe Pascale, with whom I'd hang out in Tufnell Park. How I rate this now: I enjoyed singing this live recently, but it's a little too perky and poppy. I remember Dick Green liking this at the time (Creation accountant, later head honcho of Wichita recordings). 6. Islington John: This is the only song that actually got the reggae arrangement I'd planned for the rest of the album. I think it's rather nice, actually. The lyrics were composed via Burroughs / Gyson / Bowie cut-up technique. In fact, "drunk on powdered milk and gas" comes directly from a Burroughs novel. I wrote a description of a trip to Islington and chopped it up, put the lines into an envelope, shuffled them, and put it all back together. What the technique doesn't hide is a growing sense of myself as the "bastard lover" who steals other people's girlfriends. A dangerous man to know. How I rate this now: This one prefigures what I've been doing this decade, in the sense that the narrative is a bit more counter-intuitive and mysterious. "I will pay for the fire extinguisher, the sand bucket and case if you will let me pay for this man's face", indeed! I like the climbing chorus, and the mysterious plateau it leads to at the end, with a kind of Balinese flute (actually a bass recorder) warbling. Pretty good, with Arun Shandarnikar's additional percussion (he was a bhangra drummer). 7. Three Wars: A Brel-influenced song, based around a startling mapping of 20th century wars to crises in a person's life. The odds are stacked against the person described, but he survives... well, until he dies in the last verse. I like the way the music goes up a notch in intensity at the end. "Imagine imagination dying" is a Samuel Beckett reference. "A generation lays down its life when it refuses the creation of new ways to live" contained a wink to my new label Creation (creation was my favourite word at the time), but also Ezra Pound's injunction to "make it new". How I rate this now: There's a disconnect between the song's world-weariness and apparent wisdom and the inexperience of the man singing it -- he was very green, and much more in love with life than he sounds here. What strikes me is that he really isn't "making it new" at all, despite singing about the importance of doing it. 8. Flame Into Being: Julian Standen, the American producer (he'd worked with Siouxie and The Lemonheads), loved this one, and wanted to turn it into something that sounded like the soundtrack to The Thomas Crown Affair (a sound I love too). I think he's succeeded; the rousing chorus really works. Flaming into being is really a concept from D.H. Lawrence -- I think I'd just read a biography of him called The High Priest of Love and totally identified. The 80s-topical references to black 501s are funny. The last verse breaks into a cycle of 5ths, very Windmills of Your Mind, very Michel Legrand. You can hear me hamming up the character a bit -- all the stuff about being drunk, writer's blocked, and the father of a baby couldn't be further from who I was when I wrote the song. I never got drunk, wrote too much, and wasn't in any danger of reproducing. Backing vocals here are by Louis Philippe, by the way; I think we forgot his credit on the sleeve. How I rate this now: A pretty good pop song, this should have been a single. I like the almost Morrisseyesque self-irony involved in "now the weight of the books has crushed my delicate fingers I'm not trying to be Paganini any more". As if I'd ever been trying to be Paganini! But "dreaming of sex with strangers", yes, that's what it was all about at the time; becoming what the AIDS pamphlets that year were calling a "fast-track heterosexual" was definitely an ambition. 9. Situation Comedy Blues: Before I left Mike Alway's él label I was planning a concept album about television. It was going to be called BBC1 and examine (and undermine) the British addiction to telly. There were songs about Bill Cotton, Torvill and Dean, dull documentaries. This one about sitcoms was the only one to make it onto The Poison Boyfriend. Others appeared on the next four albums (Shaftesbury Avenue, A Dull Documentary, Love on Ice), and you can hear demos of the "lost album" here. This song prefaces an important theme of my 80s albums, the question of which is more important, women or art. Those were the twin poles of my world, the things I lived for. How I rate this now: The arrangement is cheesy, I prefer the demo. You can hear a bit of the Stock, Aitken and Waterman sound I'd later develop on Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.  10. Sex for the Disabled: My big political statement about Thatcherism took the surprising line that it started when hippy ideals turned into something darker at Altamont. "The age of Aquarius changed overnight to an age of economists serving the right" -- actually, the anger at the end of this song gets the goosebumps going, together with the rousing football stadium chorus in the background. "Sex for the disabled" and "Get fit for life" were actual campaign slogans, and seemed to summarize the basic attitudes of left and right quite well. Much later Adam Curtis would develop the theme of hippyism switching over into yuppyism rather well in Century of the Self. 10. Sex for the Disabled: My big political statement about Thatcherism took the surprising line that it started when hippy ideals turned into something darker at Altamont. "The age of Aquarius changed overnight to an age of economists serving the right" -- actually, the anger at the end of this song gets the goosebumps going, together with the rousing football stadium chorus in the background. "Sex for the disabled" and "Get fit for life" were actual campaign slogans, and seemed to summarize the basic attitudes of left and right quite well. Much later Adam Curtis would develop the theme of hippyism switching over into yuppyism rather well in Century of the Self.How I rate this now: It's good, though there's too much reverb -- an 80s vice. The epic quality is a bit tongue-in-cheek, but it hits its political target with venonmous effectiveness, and reminds me of just how defeated Thatcherism made lefties feel in the 80s. I didn't join Red Wedge, I preferred to wallow articulately in that sense of political despair, of our moment having passed. I think, in Britain, it never came back. Thatcher basically won forever, because the British wanted her to. 11. Closer to You: This song is really different from the others, reflecting my love of slick UK soul band Imagination's production team Jolley and Swain, or perhaps Cameo (who I'd investigated after A Certain Ratio mentioned them), or the spoken intro to By the Time I Get To Phoenix. It's a black-sounding song (LL Cool J would later make I Need Love, which sounds a lot like this), but also reflects my shift from Brel to Gainsbourg, and to the kind of seductive easy listening songs about sex that would dominate my albums for next five years or so. I programmed the beat in my friend Douglas Benford's Roland 606 drum machine, and the arrangement builds up pretty nicely, with some great Louis Philippe backing vocals entering towards the end, as the guitars settle into a sort of slowed-down Shot By Both Sides riff. Basically this is an eight-minute long expansion of the idea Paddy Macaloon expressed when he said, on Swoon, "I don't know how to describe the modern rose if I can't refer to her shape against her clothes with the fever of purple prose". Reconstructed post-feminist men were wrestling with their sexuality in the 80s. How I rate this now: I like this song best on The Poison Boyfriend, basically because it's warm yet chilly, arch yet sincere, black yet white, and really startlingly different from anything else you would have heard on an indie label like Creation at the time. Some of the contradictions aired here (misogyny and love of women, warmth and coldness, inside and outside, mask and face) would reappear on the next album in the song Ice King, a tighter and funkier statement. The Gainsbourg "tender pervert" persona and the black sound of this music would become much stronger in my work over the next few albums, so this song is really a corridor to the future of Momus. NOTES We start with The Poison Boyfriend, recorded in 1987 by the slim Raybanned man you see in the big blue photo. It was Mr Boyfriend's second album (third if you count his stint as writer and singer in Scottish postpunk group The Happy Family), and the record that put him on the critical map in the UK. I've added a track-by-track commentary; download the mp3s by saving the links. Reviews, lyrics and interviews related to The Poison Boyfriend are here. The blue photo is by Nick Weslowski of The Monochrome Set and is an outtake from the original Poison Boyfriend photo shoot. The portrait further down the page is by Vici MacDonald, who also designed the sleeve. Vici was a writer on Smash Hits at the time; she now edits Art World magazine. Next: Tender Pervert (1988) |