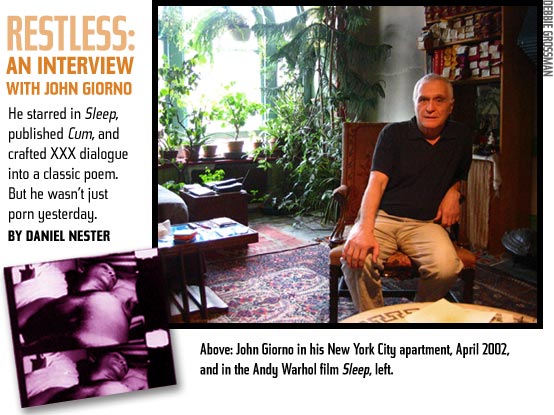

UbuWeb | UbuWeb |  UbuWeb Papers UbuWeb PapersRestless: An Interview with John Giorno (2002) (Originally published on Nerve.com) Daniel Nester

In Andy Warhol's six-hour film opus Sleep, John Giorno is the guy sleeping. He also happens to be the inventor of performance poetry, marrying technology, rock 'n' roll and pornography with an art form all too often associated with the sublime and genteel. Giorno's books include Balling Buddha; Cancer in My Left Ball; Cum; and You've Got to Burn to Shine (1994), featuring memories of his love affair with Warhol. Other former Giorno flames include William S. Burroughs and artists Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and, anonymously, Keith Haring. Now in his sixties, Giorno still lives in the Lower East Side flat he shared with Burroughs, where he played with friends like Allen Ginsberg, Frank O'Hara, Gregory Corso, Anne Waldman, Lydia Lunch, Jim Carroll, the band Husker Du and Marianne Faithfull. In a room full of Buddhist paraphernalia (Giorno lends Burroughs's old room to a weekly meditation group), we looked back on his lifelong relationship with pornography, celebrating his famous 1965 groundbreaker, "Pornographic Poem." At first, no one really said anything — it was [published in] a mimeograph magazine that went out to the downtown art world. I've never thought of this, but it was so appreciated by the downtown poets who were my friends — the second generation New York School poets — that when Ron Padgett came around to do the Random House Anthology of New York Poets, he chose it. The anthology came out in 1970.

They were all really good friends of mine. It may seem like they are all famous, but back then, they were just a little bit famous. I recorded three people — Bob Rauschenberg, Yvonne Rainer and [future New Yorker art critic] Peter Schjeldahl. I was a kid and didn't really know what I was doing. It was just a way of using sound and technology and voices. The next year, Yvonne Rainer, who really loved it, used it as a six-minute piece as part of her show at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. That was heroic of her — I mean, what was it, 1967? I kept recording and got this idea of an album, 12 people in all.

It was like a miracle — you put a microphone in front of them and one second later you'd have their whole sexual history in the sound of their voice.

Patti Oldenburg, the wife of Claus Oldenburg. Patti would be the one sewing the giant penis or the giant anything. She was very uptight! The voice tightens, the throat tightens, she gets really nervous.

Brice Marden was Bob Rauschenberg's assistant at the time, in his early twenties. I saw him all the time over at Bob's, and I just asked him to read it. Brice is straight as a pin, but somehow he just read it really great — it was sexual, he was relaxed about it. Schjeldahl, who's a bit uptight in real life, read it straight.

We were lovers for that year and a half or two years. I'd been asking him for months, and he'd say, "Yes, yes, I'll do it." We were in bed one day with terrible hangovers from endless fucking, and he went out, got home at five o'clock, and I said "Bob, you have to read that poem," and he just said, "Now." Because we had been having sex all day long, his voice was really relaxed and really juicy and really sexual. The point is that all of these people with all of these juxtapositions deal with this sexual energy.

Over time, I got to dislike poets even more!

Yeah. I mean, there you have Andy, refusing to have any gay images in his work. The art world of de Kooning and Pollock hated gay men. I mean, their wives were fag hags, and they knew a lot of gay men, but to them, a gay man could not be an artist of their caliber or on their level. Andy and Bob and Jasper were terrified that they weren't going to sell their work. They were penniless in those early years.

Yes, by being in-your-face gay, as with this poem. I chose to do it by using gay images. But my intention was not to be gay — I mean, there's such a big line between straight and gay, it's sexuality, and since I'm a gay man I use gay images. Thing is, a lot of my work is liked by women because it's not about the sex, it's about sexuality.

In John Ashbery's case, it was about winning the Pulitzer Prize, it was a plan. He's a great poet, but he won all of those prizes because he knew how to work the politics. I was appalled by that.

Oh, he's always been a fag, in your face. It only goes to show how professional he was about his career. It only goes to show how things were at ArtForum and all those publications, because if you ever mentioned anyone was gay, you'd risk being excommunicated.

I love John Ashbery, he's a great poet. But to me, one's sexuality, how one makes love, is the center of one's heart, one's life.

Sales, commerce, how publishers perceive. Something made for the straight mass market can have a little touch here or there — it has to, actually, to make it attractive. But it cannot have hardcore anything.

Because they're playing to an upper-middle-class suburban audience who are all very sexual to say the least, but it has to be straight and it has to be just a touch, little brush strokes.

Opening one's heart, whether in promiscuous sex or with a lover, a long-time affair, is the essence of sexuality. It happens, I think, more often with anonymous sex because you don't have as many obstacles or judgments about your life and habitual patterns.

Another one took place in Rome years ago. I was in bed with a cameraman for the Ed Sullivan Show, who was a handsome straight guy. We met at a bar on his day off, and we fucked for thirty straight hours. A thing of such intensity that you don't leave each other's arms, other than taking a piss or to have coffee.

It can! I have a lover now, and we have fabulous sex. It's exactly like great anonymous sex. He's an artist from Zurich, Ugo Rondinone.

The prose piece I wrote about Andy was the first prose piece I ever wrote besides letters. When powerful people die, their presence is so strong that you think about the endless things that happened twenty-five years ago. And I thought, "If you don't write this thing down now, you're going to forget."

Yes! The title of my manuscript is Great Demon Kings and Jane Bowle's Pussy. [laughs] I don't know how that's gonna make it in Missoula, but I want the pussy in there.

The story is joyous. It happens in Tangiers. She's looking at her pussy in the mirror, I'm looking at her eyes in the mirror, looking at her pussy. I didn't really realize she was looking at her pussy until later!

They're more interesting to me!

Well, I'm in half of these sections about the sex!

I know! I think a real problem I have with this book is that it's not mass market. In one section, I have thirty pages of me fucking Burroughs — in detail! The smell, the taste, what I was thinking, what he was thinking.

But the thing is, writing about this drops me immediately from the mainstream publishers. If it were thirty pages of me fucking Marilyn Monroe, it would be a ten million dollar advance. I guess I'm assuming Burroughs was as famous as Monroe, but . . .

Get the basic juices flowing first. Then you can elaborate. The secret to writing about sex is doing it with a lot of love and compassion. I mean, if you do it without those things . . . There's no wisdom or passion or love in porn, even though it's brilliant.

In my book, I try hard not to be judgmental, to make the good parts really good and to make the porn really work. The reason "Pornographic Poem" works, I think, is because it's taken out of context, it's given compassion. Compassion or awareness is put into that found work. One's awareness of one's sexuality transforms it from being ordinary, stupid porn into something else. UbuWeb | UbuWeb Papers |