|

historical historical

ubuweb ubuweb

|

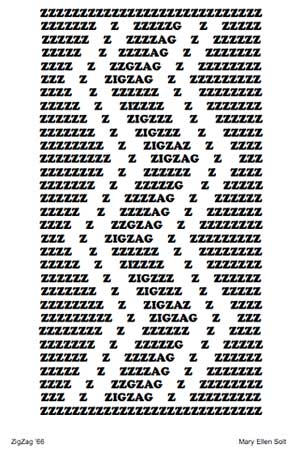

Mary Ellen Solt, USA | 1920-2007  Flowers in Concrete (1966) Complete portfolio Flowers in Concrete (1966) Complete portfolioMary Ellen Solt An appreciation by A.S. Bessa Mary Ellen Solt (1920-2007) became known in academic and poetic circles worldwide after the publication in 1968 of her influential book Concrete Poetry-A World View. Solt had been experimenting with concretism in her own poetry since 1963, after having been introduced to the movement by none other than Ian Hamilton Finlay, whom she met in Scotland in 1962. Through Finlay, and his struggling publication Poor. Old. Tired. Horse., Solt entered into contact with some of the main players in concrete poetry: Eugen Gomringer, Max Bense, and the de Campos brothers, Augusto and Haroldo. The genesis of the anthology is in many ways emblematic of Solt's approach to literature, in which formal discoveries were not entirely dissociated from events in her personal life. To use a poetic cliché, Mary Ellen Solt was "absolutely modern," a poet moving with ease between the domestic and public spheres and responding with immediacy to the events that shaped her era. In a later essay, "Memoirs of Concrete," describing how the anthology came to fruition, she credits Willis Barnstone-who had invited her to organize the anthology as a special issue of the journal Artes Hipánicas/Hispanic Arts-with improving the book's structure with his "excellent suggestions"; she also names the translators who worked under her close supervision and the two graduate students who designed the award-winning volume. Putting a book together, Solt seems to suggest, is a collective effort, and it was her openness to new ideas and the ability to bring the right people together that made her book such a model anthology. Among the many distinctive elements of Concrete Poetry-A World View, perhaps the most important was its selection of manifestos from all over the world about the new approach to material poetry. This was the first time, for instance, that Öyvind Fahlström's "Manifesto for Concrete Poetry" was published outside Sweden, in a translation by Solt and Karen Loevgren, the wife of a Swedish colleague of Solt's at Bloomington. Fahlström's manifesto had received very little attention when it was first published in Stockholm in 1953 in the mimeograph journal Odissé, and it remained virtually ignored for over a decade, until it was reissued together with a selection of his early concrete poems, in Bord (1966). Its inclusion in Concrete Poetry-A World View represented a major contribution to the elucidation of the complex genealogy of concretism. Another impressive feature in the anthology was Solt's extensive and well-researched introduction, which connected the main centers of concrete poetry, such as Switzerland, Brazil, Germany, and Scotland, to others less well known at the time, like Iceland, Czechoslovakia, and Turkey. This was no minor task, and although in hindsight some of the facts deserve revisiting, Solt's commanding knowledge of the international scene, as well as of the theory that informed the concrete program, set the tone for an entire generation that has repeatedly returned to her book not only as a source of information but also as the true document of an era that it represents. Solt's effortless rapport with concrete poetry might also explain the enduring power of the few translations that she ventured to undertake. Seven years ago, when I started to do research for an English collection on Haroldo de Campos, it immediately became clear that many of the early translations needed to be reworked-with the exception of a very few, including Solt's precise renderings of "fala prata" (speech silver), from the collection Fome de forma (Hunger of Form), and "marsupial," from the collection O âmago do omega (The Essence of Omega). Her translation of one of the poems in Augusto de Campos's Poetamenos is equally untouchable. Mary Ellen Solt seems to have found among the concrete poets a kind of extended family, to whom she and her husband Leo opened their house generously. The de Campos brothers paid a visit, and Finley remained a close friend. More importantly, she also seems to have found in their work the ideal form that she pursued throughout her whole life, which aimed to merge with the rhythms of speech the visual dimension of writing. In retrospect, the many years she spent studying the poetry of William Carlos Williams, as well as her correspondence with both Louis Zukofsky and George Oppen, seem like a preparation for approaching concretism, and in this regard, she seems to have followed Ezra Pound's advice to Hugh Kenner: "You have an obligation to visit the great men of your time." In her passionate pursuit of learning from the great poets of her own time, Solt ended up establishing a powerful network of poets and writers that perfectly captured the zeitgeist of postwar literature on a global scale. From her early essays on Williams to the anthology and later essays on Charles Sanders Peirce, Solt traced a path connecting the early objectivism of Zukofsky and Oppen to the experiments in semiotics of the concrete poets. It's interesting to note that it was among this predominantly male group that Mary Ellen Solt found her voice, a feat she achieved not by simply emulating theirs, but by bringing up themes and concerns close to her own life: the flowers in her garden (Flowers in Concrete, 1966), her husband (Marriage-A Code Poem, 1976), and her children (Solt dedicates The Peoplemover-A Demonstration Poem, 1968, to her daughters, Cathy and Susan, "who cut, sawed, painted, pasted and demonstrated").

In the fall of 2004, I went to California at the invitation of Susan Solt to research Mary Ellen Solt's papers, with the goal of editing a selection of her writings. On that occasion I also met Mary Ellen, whose memory, after a series of strokes, was fragmentary. During a ride through the Ojai valley, Susan would fill in the gaps with her own recollections of the many visitors to Bloomington and their travels in Europe, including their attempt to meet T. S. Eliot. Among all these recollections, an image of Mary Ellen printing her poem "Zig Zag" on the ironing board in their kitchen stayed with me. Considered as a whole, Mary Ellen Solt's rapport with poetry, and with concretism in particular, is reminiscent of the work of Hannah Höch, another avant-gardist of a previous era, who reassembled the events of her time through the prism of her domestic life, making her collages from scraps "cut with the kitchen knife." A. S. Bessa New York City July 2007 RELATED RESOURCES:  Author, "Concrete Poetry: A World View" in UbuWeb Papers Author, "Concrete Poetry: A World View" in UbuWeb Papers |