|

historical historical

ubuweb ubuweb

|

Kurt Schwitters | (1887-1948)

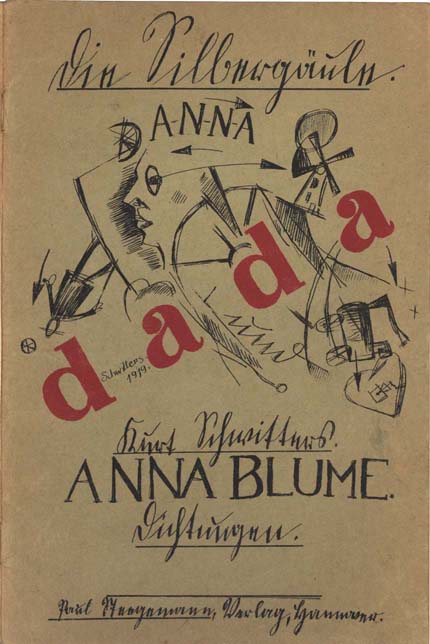

Anna Blume: Dichtungen (1919) [PDF, 104mb] Anna Blume: Dichtungen (1919) [PDF, 104mb]

Hanover: Paul Steegemann, 1919. 1st printing. 41 pages.

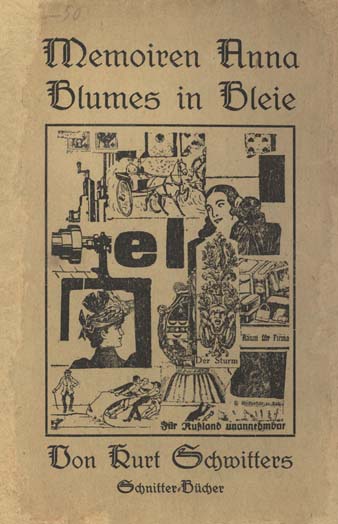

Memoiren Anna Blumes in Bleie: Eine leichtfassliche Methode zur Erlernung des Wahnsinns für Jederman (1922) [PDF, 40mb] Memoiren Anna Blumes in Bleie: Eine leichtfassliche Methode zur Erlernung des Wahnsinns für Jederman (1922) [PDF, 40mb]

Freiburg (Baden): Walter Heinrich, 1922. 28 pages. Ursonate (1922-32)  Ursonate Score Ursonate Score  MP3 versions of the Ursonate in UbuWeb Sound MP3 versions of the Ursonate in UbuWeb SoundAudio Works  Audio works of Kurt Schwitters in UbuWeb Sound Audio works of Kurt Schwitters in UbuWeb SoundKurt Schwitters is generally acknowledged as the twentieth century's greatest master of collage. Just as collage is essentially the medium of irony, so Schwitters' life is characterized by paradox and enigma. Born in Hanover, the only child of affluent parents, he was a loner in his youth, plagued by epileptic attacks, introverted and insecure, and as a student at the Dresden Academy of Art he proved as apt as he was unimaginative. Although his contact with Expressionist artists in Hannover in 1916 gave him more confidence to develop his own style, even his most impressive works (such as Mountain Graveyard) were little more than imitations of his contemporaries. A major challenge came in 1918 with the invitation to exhibit at Herwarth Walden's notorious Sturm gallery in Berlin, for Walden had contacts with most progressive European artists, including the Zurich Dada group. Schwitters found further stimulus in the activities of the revolutionary Berlin Dadaists. (The generally accepted story that Schwitters was rejected by Berlin Dada is, however, not true.) But it was Hans Arp, himself a pioneer of collage, who first persuaded Schwitters to abandon his sterile academic techniques. Schwitters' first known collage, Hansi, is strongly reminiscent of Arp's work, and soon afterwards he began making assemblages from scraps of refuse, including one he called the Merz picture. Subsequently he referred to all his work as Merz. A Sturm exhibition of his new style in mid-1919, which showed his abstract Merz works and some whimsical 'Dada drawings' (such as The Heart goes from Sugar to Coffee) caused a furore among the critics, as did his 'Anna Blume' poem published in the same year. Schwitters thrived on public opposition, and from 1919 to 1923 he created a succession of Merz pictures which are now seen as his greatest contribution to twentieth century art. These pictures carry an inner tension that derives from the sensitive juxtaposition of abstraction and realism, aesthetics and rubbish, art and life, and their innate dynamism is one of the characteristics of Merz. Schwitters stands alone in the consummate mastery of colour, the delicate balance of content and form and the intricate interplay of coarse and filigree displayed in Merzbild Rossfett; the almost minimalist Revolving, using the barest of materials, conveys a mysterious shadowy rotating cosmos extending far beyond the bounds of the frame: in Construction for Noble Ladies, the precarious equilibrium of the disparate elements is stabilised only by the side-on portrait of Schwitters' angelic and long-suffering wife Helma. Schwitters' revolution came late - he was 32 at the time of the first Merz exhibition - but Merz changed his life radically. He suddenly found himself at the forefront of contemporary art and quickly allied himself with the avant-garde, including various European Dada groups, the Bauhaus (Schlemmer, Klee, Kandinsky, Feininger, Gropius) and the new generation of Contructivists from Eastern Europe and the Netherlands (Lissitsky, Moholy-Nagy, Theo van Doesburg). By now his fantasy knew no bounds and over the next decade he undertook radical experiments in such fields as abstract drama and poetry, cabaret, typography, multimedia art, body painting, music, photography and architecture. He published a Merz magazine which appeared irregularly from 1923-32 and founded what was to become a successful advertising agency in 1924. Schwitters was a master of subtle colour and precarious balance, and during the twenties the influence of Constructivism, with its clinical reliance on primary colour and clear geometrical forms, was not always advantageous to his work. Although a quasi-minimalist approach came naturally to him (he experimented with it early, in pictures like Coloured Squares), he introduced Constructivist ideas more rigorously into his work after 1924. The composition of the Merz pictures becomes more clear-cut, the textures more uniform, the individual elements larger and simpler. But luckily he never abandoned the principles of Merz, as can be seen from the splendid Relief with Cross and Sphere and Cicero, where the effects of stark Constructivist colours and tight composition are brilliantly offset by sharp curves and shadows and Schwitters' beloved scraps of battered Merz refuse. An equally startling example is Small Seaman's Home (made in Holland, where Schwitters would comb the beaches for Merz finds during his summer holidays). For thirteen years (1923-36) he also worked on an extraordinary construction that came to be known as the Merzbau; it was what we would now call an Environment and eventually spread to eight rooms of his house in Hannover. Its original name was the 'Cathedral of Erotic Misery' and its contents were as shocking as anything produced by radical young artists today. With the rise of National Socialism in Germany after 1929, Schwitters found himself in serious difficulties. As the artistic community emigrated or went into hiding, so Schwitters was robbed of much of the impetus that was crucial to his art. The death of his father and of Theo van Doesburg in 1931 mark the start of a new phase of his work, as Schwitters himself makes clear in 'New Merz Picture', with its contemplative mood and coarse dabs of colour. The sombre restraint of Pino Antoni is likewise in sharp contrast to the works of the exuberant early Merz period. Schwitters kept a low profile during the Third Reich and emigrated to Norway in January 1937, for reasons that have never been satisfactorily explained. But the Gestapo were certainly on his trail, and in summer 1937 his pictures were displayed at the infamous 'Entartete Kunst' exhibition in Munich. Clearly his return to Germany was blocked for ever. Depressed at abandoning the Hannover Merzbau to an uncertain fate, Schwitters completed a similar construction in Oslo, but in 1940 Nazi troops invaded Norway and he was forced to flee for his life. He finally landed in England, where he was interned until November 1941. Yet the Merz pictures of this turbulent period give little indication of the fact that Schwitters suffered from poor health and time and again found himself in life-threatening situations. Merzbild Alf is often cited as an example of his brief interest in Surrealism: it is difficult to imagine that Spring Door, the superb Glass Flower and Merzbild with Rainbow, with their sparks of light and swinging rhythms, were created at a time of increasing isolation and despair for the artist. After release from internment, Schwitters lived until 1945 in bombed-out London, where the unfamiliar surroundings gave him fresh inspiration for Merz pictures. He made light of his heap of problems in Difficult, echoed the dismal fabric of wartime Britain and the blows of fate in the ironically-named Heavy Relief, reworked the great masters in inimitable tongue-in-cheek Merz fashion in Die heilige Nacht and recalled the dark days of the Nazi regime in the sinister black shapes and blood-red background of Hitler Gang (named after a film). He was fascinated by the comics sent in letters from compatriots in the USA and used them in his famous For Kate, a collage now regarded as a forerunner of Pop Art. In 1945 he moved with his young companion, Edith Thomas, to Ambleside in the English Lake District, where, financed by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, he started on a new Merzbau that came to be known as the Merz barn. At his death he had completed only one wall, now to be found in Newcastle University. Sadly, no other of Schwitters extraordinary Merzbau constructions have survived. He died at the age of sixty, poverty-stricken and neglected, but in the knowledge that his work would one day be recognized as that of a genius. As he saw, the language of Merz now finds common acceptance and today there is scarcely an artist working with materials other than paint who does not refer to Schwitters in some way. In his bold and wide-ranging experiments he can be seen as the grandfather of Pop Art, Happenings, Concept Art, Fluxus, multimedia art and post-modernism.

Through all the tribulations of his life, Schwitters stood his ground with

his

undogmatic, non-elitist and democratic creation of Merz, which conjured up

its

own magic from the rejected and the discarded: small wonder that the Nazis

found

Schwitters' art subversive and tried to eradicate it. And in our own age of

increasing extremism, his message is as valid as it ever was.

|