|

historical historical

ubuweb ubuweb

|

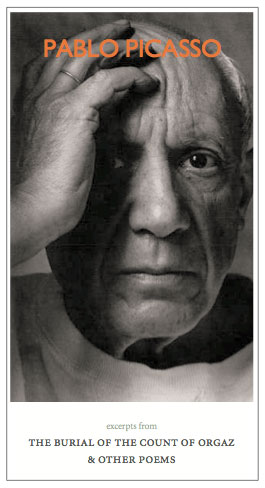

Pablo Picasso, Spain | 1881-1973

A PICASSO SAMPLER A PICASSO SAMPLERExcerpts from: The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, & Other Poems (PDF, 940k) Edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Pierre Joris. JEROME ROTHENBERG: EXCERPT FROM A PRE-FACE TO PICASSO I abandon sculpture engraving and painting to dedicate myself entirely to song. --Picasso to Jaime Sabartés April 1936 When Pierre Joris and I were compiling Poems for the Millennium we sensed that Picasso, if he wasn't fully a poet, was incredibly close to the neighboring poets of his time, and when he brought language into his cubist works, the words collaged from newspapers were there as something really to be read. What only appeared to us later was the body of work that emerged from 1935 on and that showed him to have been a poet in the fullest sense and possibly, as Michel Leiris points out, "an insatiable player with words ... [who, like] James Joyce ... in his Finnegans Wake, ... displayed an equal capacity to promote language as a real thing (one might say) . . . and to use it with as much dazzling liberty." It was in early 1935, then, that Picasso (then fifty-four years old) began to write what we will present here as his poetry - a writing that continued, sometimes as a daily offering, until the summer of 1959. In the now standard Picasso myth, the onset of the poetry is said to have coincided with a devastating marital crisis (a financially risky divorce, to be more exact), because of which his output as a painter halted for the first time in his life. Writing - as a form of poetry using, largely, the medium of prose - became his alternative outlet. The flow of words begins abruptly ("privately" his biographer Patrick O'Brian tells us) on 18 april XXXV while in retreat at Boisgeloup. (He would lose the country place the next year in a legal settlement.) The pace is rapid, violent, pushing and twisting from one image to another, not bothering with punctuation, often defying syntax, expressive of a way of writing/languaging that he had never tried before: if I should go outside the wolves would come to eat out of my handas one of us has tried to phrase it in translation. Yet if the poems begin with a sense of personal discomfort and malaise, there is a world beyond the personal that enters soon thereafter. For Picasso, like any poet of consequence, is a man fully into his time and into the terrors that his time presents. Read in that way, "the world smashed into smithereens" is a reflection also of the state of things between the two world wars - the first one still fresh in mind and the rumblings of the second starting up. That's the way the world goes at this time or any other, Picasso writes a little further on, not as the stricken husband or the discombobulated lover merely, but as a man, like the aforementioned Joyce, caught in the "nightmare of history" from which he tries repeatedly to waken. It is the time and place where poetry becomes - for him as for us - the only language that makes sense. That anyway is where we position Picasso and how we read him. RELATED RESOURCES:  Gertude Stein "If I Told Him, A Completed Portrait of Picasso" in UbuWeb Sound Gertude Stein "If I Told Him, A Completed Portrait of Picasso" in UbuWeb Sound Jerome Rothenberg, editor of UbuWeb Ethnopoetics Jerome Rothenberg, editor of UbuWeb Ethnopoetics |