| << UbuWeb |

| Aspen no. 2, item 5 |

|

|

| The Robert Murrays |

|

The Adaptable House: Instead of Limiting the Living, It Grows and Changes with Its Inhabitants By Peggy Clifford / Photos by John Macauley Smith |

|

The themes of living are love, sociability, privacy, self-expression, comfort, belongingness, and the like. They will suffuse a good house, i.e., a house willing to be suffused, with meaning. The house is no more than a receptacle to receive them... An important house is a bad house. You can tell an important house easily because it is all something or other; all Colonial, all glass, all open, all closed, all wood, all in the latest style, or all American. Such houses, because they are insistent and stuck up, prevent us from properly exercising our emotions.

|

A house that agrees completely with the foregoing is the deceptively simple Aspen house which is haven and workshop for a young playwright married to a designer & weaver — Robert and Erika Murray, and their three children. Resembling an adventurous ark gliding through a sea of sagebrush, it has no conventional lawn. A mass of flowers brightens the entrance in summer, but the rest of the "yard" is left to the caprice and care of nature. A stand of aspen trees wraps around the front of the house, shielding it from the road. The back of the house looks West across the Roaring Fork River to Aspen Mountain — an impressive view which changes subtly as the sun moves across the sky. From the deck, one is vaguely aware there must be other houses around, hidden somewhere in the landscape, but, on the whole, the vista is wild and uninhabited. The exterior, rough board and batten, is all linear and angular. The interior is highly personal and private, decorated in contemporary Murray. The living room has a wall of windows, high ceiling, white walls, and a fireplace. A graceful Victorian loveseat fits in happily with severe modern pieces and a round coffee table made from an old oak table. |

|

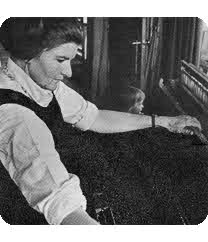

As one might expect, the studio has the best location. Beyond the serenity of the living room, it is an incredible and exciting tumble of books, yarn, records, children's toys, and an uncataloguable miscellany of things the Murrays use or merely find interesting to look at. The moment one steps into the studio, one realizes that things happen here. Its disarray is electric. Mrs. Murray's loom is there in the window where she weaves her brilliant materials in the early morning sun. There's also an ancient piano, a tremendous collection of plays, novels, and poetry, and a desk where Murray sometimes writes, though he often retreats to a desk upstairs in their bedroom, which is dominated by a complete set of the Oxford English Dictionary. The kitchen is a lively area, too, with a tumble of modern and traditional cooking tools hanging up and stacked about. Compactly arranged, it looks too small for a real cook, until you watch Mrs. Murray preparing for a dinner party. Somehow it fits her perfectly as the menu gradually takes shape on the white mosaic tile counter. Beyond the kitchen, and within easy reach, is the dining room which doubles as playroom for the children. There is a Franklin stove in the corner, and the dining room table and tall chairs are Victorian, salvaged from an old house a friend was tearing down. Many of America's leading artists, writers, and educators have dined at this table on their visits to Aspen. |

Left: The house erupts from the

|

|||

|

Upstairs are three bedrooms, furnished — more in regard for comfort and color than for efficiency or drama — with a grab bag of old furniture found in Wisconsin, Aspen, and the East. |

Left: Windbells and a weather-beaten wicker chair offer a quiet haven on the deck.

|

An eclectic art collection is scattered about the house — paintings from artist friends combined with unexpected objects like an old beaded purse, plus tapestries and paintings and sculptures by Mrs. Murray, and a striking drawing by their oldest child, Christopher. Impressively framed and matted, it resembles a Siamese scroll. A closer look reveals that it's actually several rows of vividly crayoned figures. This sort of surprise happens everywhere in the house. A vivid Tiffany lamp in the upstairs hall turns out to be a creation of tissue paper by Murray's brother, Gibbs, a New York artist. Yet there is a real Tiffany lamp in the studio. It is by no means a pretentious house. The Murrays have neither the time nor the constitutions for pretensions. It is a refreshing change from the "just so" houses that seem to be taking over America — those houses where everything is inflexibly arranged as in a museum... where you feel the hostess spent months searching for just the right bowl to adorn the coffee table... where each picture and each chair is placed in inviolable relation to one another (one much-photographed house even has markers on the floor indicating where the chairs must be placed, and woe unto the unfortunate visitor who moves one). |

|

The Murray approach is the opposite — here the house adapts to the ebb and flow of living, instead of imposing itself on its inhabitants. It is as open to change as its owners. |

|

|

||

|

The house was designed in the rough by Mrs. Murray, with architect Rob Roy doing the finished plans and specifications. The house turns its back on the road with all rooms looking toward the mountains. Upstairs (floor plan not shown) are three bedrooms. |

|

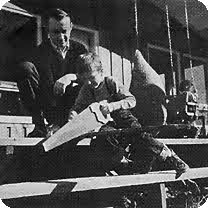

The long deck extending across the back is probably the most important "room" in the house. It is oriented to get maximum sun and warmth in winter months, and easily accommodates such diverse activities as (1) a wood-sawing project by Mr. Murray and Chris, or (2) an afternoon snooze in the hammock. |

|

|

|

|

(3) Mrs. Murray at her loom with Molly nearby. From her loom come all manner of materials — the shift she is wearing, the studio curtains, even her husband's ties.

|

|

Robert Bruce Murray, who resembles a young Alec Guiness, looks vaguely preoccupied with a secret joke most of the time. For the 1965-66 term, he is playwright - in - residence at Yale University where his play, "The Good Lieutenant," was performed at the 40th anniversary of the Yale Drama Theatre in November. It is an enviable position, given him by the John Golden Foundation, since it furnishes him the time and the finances to concentrate on the only thing he really wants to do — write plays. Like all ambitious playwrights, Murray's big dream is to have one of his plays produced on Broadway (all but one of his six plays have been produced by repertory and university groups), but he is not sure that Americans really want the theatre. "I'm probably being very pessimistic, but I sometimes have the feeling that we are forcing the theatre down American throats. If there is an American national theatre, I think it probably is the movies," he says. It was part of this feeling that led him to shepherd through the first two Aspen Film Conferences when he was program director of the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies for several years. Murray likes the discipline and limitations of playwrighting. "Things are cut down to the bare bones. You are not allowed anything extraneous, beguiling as it may be." The theme which interests him most is the inexplicableness, the devious subtleties of life. His plays do not try to solve problems, but show the world to be a baffling place where "the bad guys' and "the good guys" are constantly changing roles. Americans have a strict moral sense, he notes. "We're baffled because we're not aware of the bad things that can come from good — and vice-versa. We don't understand skepticism. And we hate to admit that it is possible to be mediocre and have no place to go. That's why playwrights like John Osborne are unpalatable to an American audience. His viewpoint is uniformly black. But it's true. And despite the truth, we don't admire people who wallow in self- destruction. Personally, I think the answer may not be in loving one another, but in knowing whom to hate." Murray is currently working on a complex drama about the ill-fated Donner party which attempted to cross the Sierras in the winter of 1846. Snowbound and starving, the survivors were reduced to cannibalism. "In my play, the leadership of Donner, a man of high ideals, is eroded by the baseness of his synchophant followers and his own ambition. It was a brave and foolish adventure which sent this band of people down to the very depths of hell and managed to bring some of them back up. I think this is the stuff of drama." For a man in his early thirties, Murray seems almost dogmatic about his principles and opinions. Erika Grob Murray has definite guiding lines, too. She wants her husband to succeed on his own terms. She wants her three children to be healthy and talented and happy. And she wants to be herself. Restlessness brought Mrs. Murray to Aspen in 1955, and she remains eternally restless. She learned to weave at the Milwaukee Vocational School and while at the University of Wisconsin achieved considerable success making men's ties out of her own materials. Erika ties were an instant success in Milwaukee's art colony. Now she also makes Erika stoles, skirts, shoe bags, and the like from her handwoven materials. She also makes all manner of offbeat things, ranging from mythic banners for announcing grandiose occasions, to immense felt blocks decorated with butterflies. Her winter project at Yale is making a group of "sewed" paintings, using all kinds of materials for her "canvas" — felt, burlap, cotton, wool, anything that catches her fancy — and then "painting" them with embroidered and appliqued designs, ranging from abstract patterns to flowers. She is a truly inventive person because she can make something out of nothing... a candlestick out of beer cans, artificial flowers out of scraps of corduroy, a shift out of burlap. Given a sow's ear and a few minutes, she probably could make a splendid silk purse. Even in her favorite outfit of sneakers, denim skirt. and Brooks Brothers shirt, Mrs. Murray has a sort of vintage elegance, yet her language is very contemporary and her interests are diverse. She's a daring skier, has a pilot's license, plays both the flute and the piano. The Murrays are a close family, unsophisticated, pursuing highly individualistic courses. Their Aspen home is a warm and boisterous setting for their myriad endeavors. It proves that a good house is only the sum of its owners' personalities. |

|

|

Original format: 18-1/2 by 24 inch sheet, black and green on tan paper, folded into covers, 4-3/4 by 6-1/8 inches. Photo credit: John Macauley Smith. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|