| << UbuWeb |

| Aspen no. 10, item 2 |

|

|

| Thou Art That |

|

Everybody is a Hindu, it's just that most people have forgotten. Hinduism is the world's oldest faith, at once mankind's most rigorous and most permissive. It rests on no ultimate authority, it admits any and all personal metaphysics, its scriptures are majestic and magical, but often erratic and inaccessible, Hinduism is a beautiful endless series of endless cycles, founded on insights and visions of eternity that may complement or oppose each other, but all are as true as each other because they all proceed from each other. In every action is contained its reaction, in every positive is contained its negative, and everything exists in terms of its opposite which exists in terms of its opposite, so that if you were to take this page and hold it up to the light and it were to burst into flame just as somewhere outside a bell rang or a cock crowed, there would be no need to believe it had happened, and whether it did, or has, it might make more sense than any Westerneducated consciousness trying to relate the most perfect mystery, the transcendental Hindu understanding that everything is God and God is everything, and any way to God is a way to God, some ways are more direct than others, but the end is always the same, however long it takes and however many detours you make. What is both consoling and commanding about Hindu philosophy is the birthright of divinity within: God did not create man, He became man, everybody has only to realise his own godhood, and that realisation is the ultimate release from the cycle of rebirth, the redemptive communion of the soul with the cosmic soul of Brahman. The supreme achievement of Hindu thought has been the discovery of Self (atman) as an imperishable unchanging entity that exists beyond time, beyond space, beyond causality, beyond all measure, and Self is the manifestation of the holy energy of the formless all-pervading God (Brahman) that animates every microcosm. In the Upanishads: "Thou art That." And all Hindu (and Buddhist) spiritual exercise is dedicated to the discovery of God within. |

Thou Art That

|

|||

|

Hindu scripture and Hindu practice indicate many avenues of devotion, many disciplines of worship, claiming authority from the ancient texts, placing emphasis and electing priorities according to their reading of them, sometimes rejecting them altogether, but the fundamental Hindu assumption of every man's potential godhood embraces all the sectarian diversity within the Hindu faith into this unity, however God is praised, the Many are the One. "The worship of different sects, which are like so many small streams, move together, to meet God, Who is like the Ocean."... Rajjab, Hindu saint. |

|

In the classical Hindu view of personal evolution, there are four aims, or ends, in life. The first is artha, the gathering of material possessions, the accumulation of wealth and family, implying all the strategies of survival, all the diplomatic cunning of private and public politics, the manipulations of power and wealth, and the texts relating to the pursuance of artha (like the Arthasastra) are every bit as cynical and sly as Machiavelli, not so much immoral as premoral. The second end of life is kama, the quest for pleasure and love. Kama is the Hindu God of Love, a playful tempter, shooting his victims with arrows made of flowers, he is the force by which the One begets the Many, and is thus the oldest god, but also the youngest because he is born every day. His is the office of creation, but also of death because the spells of delight he casts are so seductive his victims may die before they have renounced him. Like the notion of artha, kama is ambivalent, and in all Hindu and Buddhist iconography both the attractive and destructive sides of Kama are always depicted. Both artha and kama are stages that must be completed, and there is great literature, like the ambiguous classic Kamasutra, dedicated to the indulgence and mastery of these stages, even though they are both transient and illusory. |

|

The third aim is the complex notion of duty, dharma, the laws of moral action and religious ritual. Each caste has its own dharma, and the whole concept of caste depends on the acceptance and realisation of each individual's role within the organism of society, not an appealing system even if you approach it from the ruins of democracy, but founded on the sensible assumption that there are no accidents, the law of karma destiny, your life is plotted by your karma and dictated by your samsara (all the consequences of your past actions, the cumulative karma of your past lives). Dharma, the philosophy of duty, the divine moral order, also indicates four life-stages (asrarna). The first is that of the student (brahmacarya), commanding strict chastity and unquestioning obedience to the master. The student then graduates to the second stage, that of the householder (garhasthya), during which time he marries, raises his family, serves his profession and applies himself to the mastery of artha and kama, and his social duties of dharma. In middle-age, as his sons accept more familial responsibility, he enters the third stage, that of the renunciation of worldly goods and worldly roles, the renunciation of artha, kama and dharma, and departure to the forest (vanasprathya), to seek the discovery of Self, in preparation for the last stage, that of the wandering holy beggar identified with the eternal Self (sannyasa). "He no more cares whether his body, spun of the threads of karma, falls or remains, than does a cow what becomes of the garland that someone has hung around her neck; for the faculties of his mind are now at rest in the Holy Power (Brahman)"... Samkara, Vedantist teacher. |

This life stage corresponds with the fourth aim of life, moksha, spiritual release, redemption, transcendence, the paramartha (paramount object) of the Hindu faith. Hinduism is visionary, it is beyond logic, beyond grammar, and can only be expressed metaphorically. But the metaphors, the translogical reality of symbols carry the insightful knowledge of the sage to the Hindu masses. Thus, popular Hinduism appears polytheistic, in the particular worship of the mythological pantheon, but it is in fact monistic, because each divine incarnation (avatara), each He, is understood to be the One. So, along the path of devotion (bhakti), though one temple is to Rama, another to Krishna, another to Kali, all the adherents are committed to the same belief. (Among the gods, the supreme triad is Brahma, the creator; Vishnu, the preserver; and Shiva, the destroyer, and thus the creator; and they all have male and female sides). Hinduism is more a matter of conduct than dogma, it embraces monism, dualism, monotheism, polytheism, pantheism, even atheism (the hobo Bauls of Bengal have no temples, no gods; for them every moment is a moment of worship, wherever they are is a shrine). The orthodox Hindu holy texts begin with the four Vedas, dating from the second millenium B.C., ancient collection of prayers, hymns, and ritual formulae. The Rig-Veda records the hymns and mantras, in praise of the Vedic pantheon; the Sama Veda records the melodies; the sacrificial formulae are contained in the Yajurveda; and the magical formulae in the Atharveda. The Vedas arose out of the intuitions of primitive natural science, the observation of, for example, fire in its many forms, leading to the postulation of one spirit pervading all life, and all phenomena being merely illusory (maya). |

|

|

The universe is accepted as a continuous transformation of opposites through the relentless dynamism of the everlasting universal holy power, so that pain and death are accepted, even sought, to balance delight, because the totality of the cosmic dance of creation and destruction, is not only accepted, it is fervently adored. Each man, in his daily round of waking, sleeping and dreaming, contains the entire macrocosmic cycle of creation and destruction. Slowly, though, the introspective path of knowledge (jnana), access to the imminent spirit through knowledge, replaced the path of ritualistic activity (karma), when the abstract philosophy of the Upanishads, despite side trips into arbitrary cosmology, no longer dwelt on magic and sacrifice, the only magic being the power of truth, and the miracles achieved through holding to truth (satygraha), a notion Gandhi invoked when he put the true way of karma into practice against the British. |

The unity of Brahman and atman, of holy power and Self, is first suggested in the Vedas, but it is in the speculative philosophy of the Upanishads, which date from about 800 B.C., that the pure articulation, "Thou are That" emerges. Braham is: "Hidden in all beings, all pervading, the self within all beings, watching over all works, dwelling in all beings, the witness, the perceiver, the only one, free from qualities. He is the one ruler of the many who seem to act but really do not act, he makes the one seed manifold." (Sevetasvatara Upanishad, VI, 11-12). The forms of Self are accidental, just like a jar is an accidental form of clay, and the forms also are fragile, perishable, so that a jar may break, but still the clay remains. And in order to discover the Self, you must attend not to the forms of the exterior world of the senses, but look inward to the soul. |

|

"The Creator, the divine Being who is self-existent drilled the apertures of the senses so that they should go outward in several directions; that is why man perceives the external world and not the Inner Self. The wise man, however, desirous of the state of immortality, turning his eyes inward and backward, beholds the Self." (Katha Upanishad, I IV, 1). The third classic Hindu document is the Bhagavad-Gita, the Song of the Lord, an allegorical dialogue between Arjuna, the warrior, and the divine incarnation, Krishna, his charioteer. In the Gita the two traditions of Indian philosophy meet, the monistic Brahmanical principle articulated in the Upanishads, and the other ascetic intellectual disciplines of Jainism, Sankhya, and Yoga, which share a dualistic concept of life and matter, an opposition between the pristine potential of the individual, and the impure processes of nature that must be purged by will. The composite Gita is the first text of rapprochement between these two traditions, and remains the most popular and authoritative text in Indian religious life. "Some, by concentration, bent on inner visualisation, behold, through their Self, in their Self, the Self Divine; others behold it through the Yoga technique related to the Sankhya system of Enumerative Knowledge. Others again, however, not knowing the esoteric ways of introvert self-discipline and transformation, worship Me as they have been taught in terms of the orthodox oral tradition; yet even these cross beyond death, though devoted exclusively to the revelation as commended in the Veda." (Bhagavad-Gita, 13, 24-25). |

|

The Hindu God is no jealous God, he welcomes every variant faith and creed dedicated to enlightenment, he is both loving and indifferent, possessed of no ego, he issues no wringing commandments like those in the Old Testament, he makes, none of Allah's totalitarian demands, he is a re-; flection of all forms of worships, and all ways to God have their own truth, because they are the exercise of the God within every individual,", whether he realises it or not. "Whosoever seeks to worship whatsoever divine,,, form, with fervent faith, 1, verily, make that faith, of his unwavering." The Hindu sages, the prophets and the saints, have defined and redefined the conceptual and behavioural assumptions of orthodox Hinduism, located and relocated emphasis in the texts; some Vedantist teachers have insisted on a rigid monis tic interpretation of the Upanishads and the Gita, others, like Samkara, have pursued more empirical notions of the relation of the senses to the suprasensory Self; incarnations, like Mahavira, the,, prophet of Jainism, and the Buddha, have consolidated distinct sub-Hindu faiths; some have approached Hindu cosmology (and even the doctrine, of reincarnation) as mythic and metaphorical rather than actual — there is, and always has been divisiveness and factionalism within Hindu theol- ogy, some of it eccentric, some of it purely semantic, but persistent through milleniums of Hindu history is the magnificent formulation of "Thou art That." In the West today, the culture of the East is pillaged and adored, misunderstood, vulgarised, and sanctified, in a bunrush for a dollar's worth of enlightenment. I remember my mother in her leotards grappling with the lotus position before a' spritely young lady guru on afternoon television. In London, New York and San Francisco rotting cigarettes made of leaves in the backstreets of Calcutta that even the beggars grumble to smoke are a big number in psychedelic storefronts among modish hippies in Indian shirts and Indian sandals, rolling joints with Indian papers while they burn Indian incense and listen to a morning raga after dinner. Indian craftsmen can't turn out sitars fast enough. The acceptance of Indian culture more often than not surrender to fashion, and too, few are likely to apply themselves to an understanding of the Hindu religious heritage. Perhaps it's a shame, but it doesn't really matter, the culture and the convictions of India are indestructible, and though the meeting of East and West may be more like a blind date than a gracious introduction, it is a happy meeting that must evolve beautifully as increasing numbers search through the mysteries of physical and spiritual exercise towards an intimation of the eternal Hindu aim of tranquillity and self-discovery. |

|

|||

|

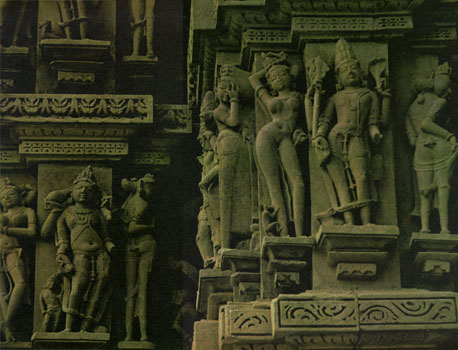

Meanwhile, Western orientalists have reinterpreted Hindu thinking in terms of twentieth century psychology, and domesticated the discovery of the Self, preferring to think of it as a perception of the illusoriness of social values, rather than the orthodox Hindu and Buddhist doctrine of maya, the utter illusion of all phenomena. So that moksha may be thought of as a release from the mundanities and deceit of materialism, or at least a release from believing them to be the true way of the world, rather than a release from the flesh. In other words, moksha is getting hip to the games people play. True holiness has been led down from the mountain top and into the marketplace, where the enlightened individual may, willingly play the games around him, secure in his understanding of the rules, but never naive enough to think of them as the reality. Such ecumenical interchange has prompted similar revisionist thinking in India, (and prompted also occasional shocked retreat into revivalist Vedic fundamentalism) ) The mysteries remain untamed, as they always have. Sooner or later everybody must confront them, sooner or later everybody may discover pure self-conscious play. The confrontation with Hinduism is the invitation to find out for yourself — MICHAEL THOMAS Photographs by Kenneth Metzner ©Aspen No. 10, Section 2 |

|

Original format: Single sheet printed on both sides, 33 3/4 by 9 inches, folded into thirds. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|