| << UbuWeb |

| Aspen no. 10, item 4 |

|

|

| Indian Miniature Paintings |

|

Indian Miniature Paintings |

Text and Photos by Allen Atwell |

|

Of the three high gods of the Hindu pantheon — Brahma, Shiva and Vishnu — Vishnu is known as preserver and supporter. Yet all three gods are identical in their ultimate substance and each reflects within himself the polarities of manifestation. So Brahma is the creator, but he also traditionally expresses being beyond all limitation. So Shiva is the destroyer, great lord of ascetics, teacher of the scriptures which lead us to transcendence. At the same time Shiva and his goddess prevail in the image of fecundating union, as procreating father and mother of the universe. The paradoxes of Vishnu's all-encompassing nature seem less dramatic than those of Shiva, at once linga and naked sadhu, yet Vishnu too necessarily encompasses all aspects of the manifest, and he too periodically assumes the role of destroyer, annihilating the universe of his own creation. In the mid-eighteenth century Bundi painting on the cover of this booklet [shown at right], Vishnu appears in his boar avatar, Varaha. Varaha saves the newly created world from a titan who has seized her and held her under the cosmic sea. By his tusks he supports the earth well up out of the water on a crescent moon. He himself is supported by the demon he has put down — one of the most delightful demons ever invented! Private Collection. |

|

|

|||

|

In this eighteenth century Vaishnava painting from northwest India, portraying the Hindu creation (preceding page) [shown above], we see the god Vishnu and his consort, Lakshmi, supported by the seven-headed serpent, Ananta. Ananta (endless) is their couch on the cosmic ocean. From the sleeping god's navel springs a lotus on which sits the four-headed Brahma, the creator. One day of Brahma is calculated to be 4,320,000,000 human years. The gods and goddesses observe each other while behind Lakshmi, like an aspect of her consciousness, stands the sage, Markandeya. He has spent eons roaming through the worlds which are the dreams of the sleeping Vishnu. Here we see him also observing the creation of the creator. |

As we begin to assimilate the notion that all manifestations are Vishnu's dream, we experience ourselves and all environments as within the body of the great god. It is possible to see that one enters the higher creative process by entering the stem of Brahma's lotus at the navel of Vishnu from inside the god in just the same way as one goes up the elevator in a tall building. This is referred to as manifestation in the solar plexus, the image of Brahma indicating how manifestation takes place in time and space. Lakshmi is the reflex of Vishnu. She supports and massages his right foot, the abode of deepest consciousness within divine consciousness. Collection of the Kalabhavan Banares Hindu University. |

||

|

Durga Mahisamardini. The Goddess Shakti in her form as Durga (she who is difficult to go against), conqueror of the buffalo demon, Mahisa, is shown on the following page. Mahisa, by his austerities, has come to control the cosmos and is tyrannizing over the helpless gods. The demonic force has reached such proportions as to threaten the cosmic harmony — the various gods, with Brahma at their head, appeal to Vishnu and Shiva. Wrathful, these two high gods pour flames from their mouths, as do the others, and from the single cloud combining the fiery energies of all the deities emerges the form of the goddess with eighteen arms. The powers of each of the gods are assigned to the goddess, who is the unconquerable Shakti. She rides her lion, fully armed by all the deities for the destruction of Mahisa. In this most delicate rendering of the oftenpainted theme, she performs the feat on a high plateau above the plains of northwest India. The scale of the landscape is made mysterious by birds. The hosts of goddesses and demons are not shown. Private Collection. |

|

|

Krishna, the most popular incarnation of Vishnu as hero and lover, is the predominant subject for painters of the period of the Indian miniatures, the late seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries. Here, as a divine seven year old (page 9) [shown at left], he is the subduer of Kaliya, the serpent king, who has become overpowerful and poisoned the river Jummna (pingala). This Kangra Valley painting renders the climax of the vanquishing, when all Kaliya's daughters make offerings to Krishna, imploring him to spare their father's life. He will agree, upon condition. Deity arises to any disturbance in the cosmic process as subduer, integrator, and guide. This painting, like the Durga Mahisamardini, gains much of its beauty and charm from the incongruity of its scale and the scale of events it refers to. Collection of the Kalabhavan Manares Hindu University. |

|

On a very hot afternoon in the region of Bundi in an eighteenth-century summer garden, Krishna is seen tossing garlands toward Radha and her friend, who, seated on the wet marble in silk saris, coax the fish with tidbits (page 12) [shown at right]. Krishna, the teacher of the Bhagavad-Gita, is often shown approaching in some way his beloved Radha. Here we are given a vision of the divine lover intent upon his desire on this simmering summer's day, the hero in search of the perfection of his soul. Krishna is invariably painted blue, as is Vishnu, of whom he is an incarnation. Collection of the Kalabhavan Banares Hindu University. |

|

|

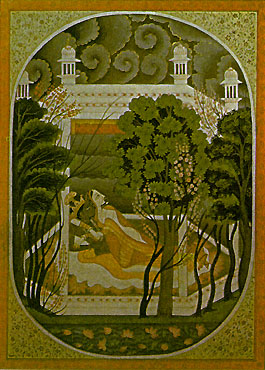

Radha and Krishna on a bower of lotuses are disturbed in their play by a rising storm. They are painted in the early nineteenth century in the Kangra Valley style (page 13) [left]. Their bower is a roofed and turreted garden pavilion beside a tank full of lotuses. The blossoming tree entwines around the larger tree much as Radha winds about Krishna. Verses from the twelfth century from Shri Jayadeva's Gita Govinda tell of such a night: She performed as never before throughout the course of the conflict of love, to win, lying over his beautiful body, to triumph over her lover; And so through taking the active part her things grew lifeless, and languid her vine-like arms, and her heart beat fast, and her eyes grew heavy and closed; For how many women prevail in the male performance! In the morning most wondrous, the heart of her lord was smitten with arrows of love, arrows which went through his eyes, Arrows which were her nail-scratched bosom, her reddened sleep-denied eyes, her crimson lips from a bath of kisses, her hair disarranged with the flowers awry, and her girdle all loose and slipping. With hair knot loosened and stray locks waving, her cheeks perspiring, her glitter of bimba lips impaired.... Private Collection. |

|

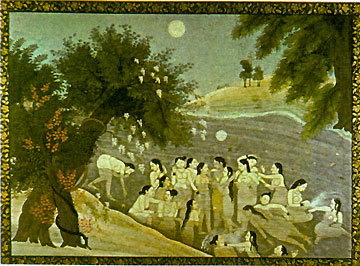

Krishna and the Gopis bathing in the river on a full moon night (page 16) [right]. The trees in the painting's right are among the most ecstatic trees ever painted. Everything participates in this divine play of the divine couple in which all the females seen are seen as reflections of the most beloved Radha. Radha is mortal and the perfect embodiment of Krishna's feminine half. Their play is based always on their desire to be again alone together, free to express their love to each other in what ways are agreeable to both, forever. Collection of the Kalabhavan Banares Hindu University. |

|

|

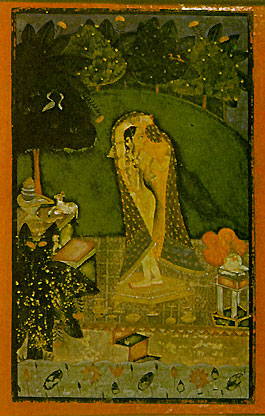

Bhairava Ragini, Bundi, eighteenth century. She stands on a golden dais, selfilluminated in the night (page 17) [left]. She is about to bathe in the lotus-filled pool before attending to her worship of the linga and yoni. Or is it after the bath and after her ritual attention to the Shiva shrine, at a moment when her attention is distracted by a sound in the night? The ragini form is based on a tradition of musical and visual equivalents, a ragini being a variation on one of the six basic ragas, or musical modes. In both music and painting, certain subtle perceptions arising from mood and situation are rendered by variations on a well-known theme. Private Collection. |

|

She stayed on the roof searching for her expected lover until the very breaking of a violent storm (page 20) [left]. This early nineteenth-century Kangra work shows her hurrying off the roof as the storm begins. All of the elements are thought of as symbols for the state of affairs between the two lovers. Collection of tile Kalabhavan Banares Hindu University. |

|

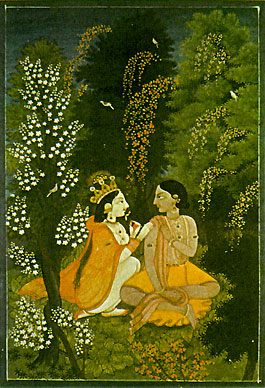

In this exquisite painting (page 21) [right] Radha and Krishna have exchanged roles and clothing. The intensity of their love has got them past all notions of separation. Undisturbed by the songs of birds in a magic springtime, they gaze lovingly in full trust into each other's eyes. This is the perfection of the dual state which precedes the gestures of union and the experience, on earth, of ecstatic bliss. Here we see the divine passion to be with the beloved as one, never one more than the other, never one less than the other. Each is always both. Collection of the Kalabhavan Banares Hindu University. |

|

|

Ardhanarisvara, Mandi, eighteenth century, page 24 [left]. Here is a painted example of Shiva and Shakti in one body. As the story is told in the Puranas, one day Shakti saw herself reflected in the mirrorbright breast of her husband. jealously she mistook her image to be that of another, preferred, woman and she and Shiva fought. Once reconciled, the goddess wished to be so united with her lord that she could never again suffer the feelings of separation. And so they allowed their bodies to merge. In this version, the right, male side, is light and carries the attributes of Shiva, while the left, female side is dark and carries the attributes of Vishnu. In describing the sequence from unity to multiplicity, the image depicts the point before differentiation of the divine pair as separate bodies. On the return sequence toward the recognition of two in one which is, in fact, the condition of each on a psychic level. The figure spins on the center axis where duality even within one body disappears. Each is both half mother, half father, and when that duality is resolved, one experiences the self as unique, infinitely complex, at once awful and beautiful. Private Collection. ©Aspen No. 10, Section 4 |

|

Original format: Twenty-four page booklet, 4 by 6 inches. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|