| << UbuWeb |

| Aspen no. 1, item 2 |

|

|

|

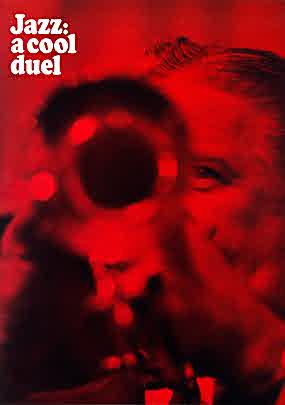

Jazz: A Cool Duel

For accompanying audio, listen to item 3 |

|

Give me the happy sounds of Dixieland,

Now wait a minute, Dad;

Just what is this thing

|

|

Give me the happy sounds of Dixieland,

I doubt if any word in the English language is more capable of saying less about as many different subjects than the word "jazz." The word seems to have been originally used in referring to the peccadillos of procreation. It was spelled "jass" at that time and one would think of it as an entirely different word, except that the first jazz band ever to record used it thusly on their first recordings: "The Dixieland Jass Band." The Victor Recording Company by using the language of love in identifying their product extended the usage of the word to denote peccadillos of music. After the first few records, the word was changed to jazz and since then it has been used indiscriminately in referring to anything and everything, no longer confining itself to the coverage of biology and music. The term "all that jazz," meaning something on the order of "stuff and nonsense," illustrates pretty well the latitude of potential involved. |

|

|

However, it must be granted that in its employ as pertains to music, usage of the word is stretched to its utter dimension. The word "pole" is used in alluding to opposite ends of the earth, for instance, and depending on which end one has reference to at the time, that end is properly and gracefully classified with a proper prefix, such as north or south, as the predicament calls for. This is done to somewhat relieve anonymity. Not so in music. Jazz is Jazz. The happy sounds of Dixie and the morbid laments and cliches of progressive (?) jazz (?) are lumped as one. Couldn't we at least have a north jazz and a south jazz? It seems that contemporary music, having become the antithesis of what the term "jazz" originally implied, would deserve some definite category. First, they called it bebop, then they called it rebop and then bop and then, either to give the mutilation meaning or to further the confusion, they called it jazz. But it's like I say, jazz is jazz. On occasion, writers will refer to the product as "sound." These cats are getting close — one step farther and they'd have made it. It has always seemed to me that instinct should be the criterion of jazz, in its rendition, as well as in the listening. Today, analysis, strategy and science have become everything. Two and two is four, man. Don't Juilliard and Berklee say so! |

Sure enough, you can travel in space, using mathematics as a springboard, and you can produce music with an I.B.M. machine, but in my book, the boys in the Model Ts didn't do too bad by ear. I've seen a performer under this contemporary approach virtually wear out a trumpet in one chorus, playing everything from a bass part to a piccolo part on the same instrument. Man, was I amazed! However, I'd much rather hear a guy like Beiderbecke play just one note, within the staff, or anywhere else for that matter. Jazz is Jazz. Mostly, I guess it's what people think it is. Some think it's taking a horn apart and putting it back together in one chorus of sixteen measures and some think it's holding a long, high note (preferably a little flat and without vibrato) for thirtytwo measures—and the longer you hold it the sooner it'll fit. And techniques? Wow! But it's like Joe Marsala once said—"If you don't care what notes you use, who can't have a technique?" The distance between notes has always seemed of importance to me—both up and down and sideways. Nowadays, they just bunch 'em up in all directions and goddam! |

|

MY FAVORITE WAY OF listening to most of today's output is with a pair of tight-fitting earplugs and a pair of dark glasses, so you can't see anything much either, and then proceed to get loaded. Rock and Roll has something, though— namely, the dancers—and one can get his kicks out of trying to think up some practical use for the twist. It wasn't too long ago I attended a jazz (?) session in the modern idiom and had forgotten my dark glasses. Here are these cats, black glasses by the square foot, and wall-to-wall beards and they're playing the blues in B flat in the key of A. That is, they're playing it in B sharp and A at the same time. This is jazz, man, but only half as good as when they get all screwed up. How they can tell when they're all screwed up, I don't know, but they can tell somehow and even through the beards and dark glasses you can tell they're all cheered up — soul music avant garde! Now that they're completely fouled up and nobody knows where the hell they're at (except the audience) they really get crackin' and things get better all the time as anything fits anywhere and everything sounds the same as it did in the first place, except more so, and louder, which is really impossible, so the saxophone player evidently gets to feeling rather hopeless and casually drops out and one of the other guys, seeing this, figures it's the end and also drops out. This is a hell of a good chance for the piano player, who hasn't been heard so far, and he bats his brains out for an indefinite period whilst the dropouts sit there growing beards. |

Suddenly, but not too soon, the boys find out where they're at and figure it's a good time to have an intermission—while they're ahead. So this is what they try to do and in trying to stop they get so really fouled up it sounds like a special ending and this inspires the drummer to a fifteen minute solo. The rest of the band sits there and pick their noses, etc. for a quarter of an hour. Now the trumpet man takes off on a cadenza as a signal that the drummer is through with his solo, which everybody accepts except the drummer, so now the only thing left to do is to try to drown out the drummer, which they finally do, and now after another ten minutes of trying to find out who's got the ball, they finally get the ducks back in the pond and an intermission is had. They all meander over to a table where sits a chick (with dark glasses) who looks like an offspring of Lady Macbeth by Dracula. A round of introductions takes place wherein all the boys smile, thereby showing their teeth and giving their faces a much needed biological identity, and become seated, which offers another clue. Nothing much happens now for awhile and they just sit looking as if they'd just gotten through with inventing a tea kettle with a whistle on it, or something, until one heads for the powder room, another toward the bar and another for the cigarette machine, whilst the fourth one remains at the table with this Charles Addams weirdo and gazes into her eyes through two thicknesses of dark glasses — his and hers. Being in no mood to hear "How High the Moon" again in a multitude of keys simultaneously, I have me another snort and powder out before I have to call a tug boat to get me home. As time goes by, I try to keep "tripped up" (that's the latest for "hepped up") by reading musicians' magazines and it seems that night clubs everywhere, generally speaking, are closing their doors or eliminating live entertainment. Personally, I think a few less beards and a little more music would tend to alleviate this situation. |

|

Now wait a minute, Dad;

|

When Freddie Fisher says, "I doubt if any word in the English language is more capable of saying less about as many different subjects than the word "jazz", he speaks more intelligently on the subject than many a so-called "jazz critic" has. I don't know about you, but that's my view. I take the position that the only critic of music is the musician. Continues Freddie: "The word seems to have been originally used in referring to the peccadillos of procreation." This statement contains a great and important revelation and I would like to delve into it in more depth, by way of explanation. In a work called "Evolution of The Blues," in which I had my say, I said it this way: |

JOHN COLTRANE (top)

MILES DAVIS (center)

HORACE SILVER (bottom)

|

"Now, in New Orleans when the French flag was unfurled, the Crescent City was known as 'The Paris of The New World,' a city wherein right from the start there was plenty of culture music, and art. "And in the evenin' when the work was done, the French let the slaves have a little fun. They blew a castoff horn and played a broken drum and let the rhythm cut loose some. And they always sang. They sang in the fields in the heat of the day. They sang in the evenin' when the day went away. They sang of work and earth and sod. In a brand new language they sang the praises of God. 'Though the church was new and the language was too the feelin' of children is always true, so the spirituals became the way of expressing the hope of a better day. 'Steal Away' could be taken differently if three or four of the children turned up missin' the very next day, and 'Swing Low, Sweet Chariot' made many a sad eye gleam when it meant that the Underground Railroad was runnin' full steam. Through spirituals the children could send messages while workin' with their shovels and hoes right under the master's nose. "Now, cities are sinful. There ain't no more to it. If you ever get a chance to move outa one, do it, 'cause when the children got to the cities they still sang the music of the church, but the words they was singin' left the church in the lurch. In the church, women are called 'Sister' and the music had no hues, but out side the church women became 'Baby' and the music became the Blues. Or, as the scholars would say: Spirituals are the music of earth and sod expressing the slaves' belief in God. Blues are the music of suffering and strife expressing the secular side of life." Now, don't ask me why they're called the blues, 'cause I don't know why. The only thing I do know is that Man on Earth is surrounded by sky, and the sky is blue, and from the blue sky the blue sea gets its hue. And when you stop to think about it some, even the blackest night ain't really black. It's dark blue! So, when you sing spirituals outside church, you gotta pay earthly dues so they become the blues, and when you play 'em on a horn a new music is born, a music that became very popular because of its infectious rhythm. Wherever it was played the players got the people swingin' with 'em. If you don't believe that's so you must've forgotten when they threw stones at Richard Nixon in Venezuela and a week later threw flowers at Satchmo. John Foster Dulles may have been Secretary of State but it was Satchmo who salvaged many a State Department date. And I certainly must include in this piece the fact that Dizzy stopped an anti-American riot in Greece. But for reasons too degrading to mention, this musical invention was removed from places like Congo Square, where people came from as far away as Europe to enjoy it there, and placed in houses of prostitution. Under those circumstances it became pretty hard to acknowledge it as a cultural contribution. This is what Freddie Fisher means when he speaks of "peccadillos of procreation." The chicks involved were not interested in procreation, but sensation. No one can refute the fact that the music which had been born in church had been systematically relegated to houses of ill repute. And the word "jass" or "jazz" didn't—and still doesn't, refer to the music at all, but to the sexual activity engaged in by the girls on call. American musicians— older and newer, still have to labor under the onerous connotation of a word that is less descriptive of music than of a sewer. In every American city it's still the norm to erect expensive opera houses glorifying a European art form. |

|

Yet, the young cats are the spiritual children of the old cats, and if the old cats don't like what the young cats do they really can blame no one but themselves, and I sincerely believe this to be true. It's comparable to the careless, immoral parents of today who do anything they care to, then refer to their children as "juvenile delinquents" when they do the things their parents do. The father is supposed to guide the child, but some of the old cats cut up pretty wild. Okay, so the only places where they could play the music was in joints where whiskey was sold by the cup, but did the old cats have to try their best to drink it all up? If a man is alotted 70 years in the Bible before he draws his last breath, how come so many older cats used to drink themselves to death? Just what is the difference between an old cat who takes a drink wherever and whenever he can grab it and the young cat with a heroin habit? Everything's faster these days, and heroin's quicker than liquor. Both seem, to me, a crime. Perhaps the difference is one of time. Still, I agree with Freddie that the average old cat is more musical and mellow than the average young fellow. At least in the old days the only experts were the musicians alone. Nowadays "critics" are crawling out of the woodwork and many of them have become widely known. And the service these "critics" have rendered to the art form they pretend to criticize is that they have cut it up more ways than two boardinghouse pies. Just what does the term "progressive" mean? Does it mean Stan Kenton playing atonally and dissonantly loud enough to draw a crowd, then, when everybody got hip to what was goin' on in his head, quittin' the scene declaring, "Jazz is dead"? But he met his Waterloo and time was his Wellington. Long live Duke Ellington! And what about the young cat who is advised by critics that he should attend schools to learn where he's at? There's an old saying: "If you don't like it, you can lump it," but to me it's downright silly of a young cat to walk past Louis' and Dizzy's and Bobby Hackett's house on his way to learn how to play the trumpet, or to pass Coleman Hawkins with his axe on his way to learn how to play sax. When it comes to this music we unfortunately call jazz, these men and others are the only schools, and students of this music who learn in any other are fools. However, blanket condemnations of "modernists" are dangerous, 'cause you might overlook the contributions of the cats who have attained high position because they have carried forward an old and honorable tradition. I refer, in the main, to Miles Davis, Horace Silver and John Coltrane. About Miles we need not waste word. He is out of Diz via Bird. His playing sometimes attains a poignancy that moves one to tears. He is the most individual trumpet stylist in years. One could not refute this if he tried. It cannot be denied. |

|

|

Just what is this thing

|

Freddie Fisher and Jon Hendricks have attempted some definition of what is apparently a confusing word. Mr. Fisher tries an etymological analysis of the word "jazz" and Mr. Hendricks tries to pin things down by some history and naming of names. Here is the most concise working definition of the word "jazz" that I can come up with (it is far from the most complete): Jazz is a method of making music. It is a method which produces a music with a characteristic highly syncopated rhythmic feeling. It usually has room for improvisation within the framework of the harmonic structure of the piece as laid down by the bass, piano, and/or guitar, which, together, provide a kind of contemporary basso-continuo foundation for the music. |

LOUIS ARMSTRONG

JACK TEAGARDEN

BARNEY BIGARD

DIZZY GILLESPIE

|

While this may seem to be a broad definition, at least it excludes what is not jazz. Anything contained within the boundaries of this description is jazz of one sort or another. This definition excludes evaluations. It does not tell you whether the music is good or bad. Dixieland and progressive jazz both fall within this definition, along with all the other myriad kinds of jazz music. Discussions of these particular musical differences are questions of style. The word "Dixieland" describes certain easily recognizable characteristics of a music. There is a more or less typical Dixieland instrumentation: at least three horns in the front line—usually clarinet, trumpet, and trombone —and a rhythm section that may include banjo and tuba. The melodies and their embellishments are of a predominately diatonic nature, the harmonies are essentially triadic in character, and the rhythms are felt in simple and clear syncopations against a two-beat (to the bar) rhythm section. Besides this, there is a characteristic ensemble formula which is often heard in Dixieland bands in which the trumpet plays the melody, often quite freely; the clarinet improvises an eighth note obbligato over the melody; and the trombone plays a bass line in half and quarter notes (sometimes called "tailgate" for reasons that make a picturesque story but are tangential to the musical facts). Not all of these characteristics at once are necessary to make a Dixieland sound; remember, now we are talking about a "style"— an amorphous, changeable combination of ideas and executions which is only vaguely defined and whose boundaries defy solidification. The best we can do to suggest what this style is like is to aim somewhere around the middle and take a pot shot. What is called "progressive jazz" also covers a multitude of sins and saintly acts. It is bounded on the rear guard by some things called "mainstream" and "swing music" (notable as the only famous monarchy in the usually democratic music world); on the avant-garde by many noise makers and happenings makers but too few music makers (I have never been able to figure out what those happenings makers were good for since happenings seem to be happening all the time without their precious assistance); and flanked on all sides by commercial musics which borrow from its vocabulary, like Bossa Nova, American popular music of many kinds, and even a companion blues music with which it shares a mutually nourishing relationship. I've taken a shotgun blast all around the shape of progressive jazz because the center of it is so busy with variants that it is harder to characterize than Dixie. However, there is a rich musical vocabulary available within the progressive jazz styles which make use of a multitude of subtle shadings of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic relationships. These variations, within the style, are so profuse that to say that the melodies are chromatic, the harmonies based on complex chords, and the rhythms highly syncopated is not very helpful. All that is generally true. Jazz has moved and changed style at an amazingly rapid rate trying to catch up with centuries of development in classical music in the short space of about sixty years. Whether or not it has "progressed" is not exactly the question here. A more complex style is not a guarantee of better communication and artistic results. Mr. Fisher has a preference for one style of jazz music—Dixieland. He describes a jazz session of the most unattractive, anti-social, uncommunicative, and formless sort and then labels it "progressive." The musicians that Mr. Fisher heard may well have been just as bad, if not worse, than the picture he paints of them. They may even have been playing in a modern jazz style. But the essential fact is that they are bad musicians—not that they are progressive jazz players. The characteristics of any good music fall into two general categories: those which convey emotional qualities, and those which convey a sense of form, giving the emotional content a shape to ride on and helping to make the feelings understandable to someone besides the person who is playing. The most important thing about the emotional qualities is that they must be there. The artist must be in intimate contact with those spontaneous elements of his personality in order to give a creative and meaningful performance. |

|

The formal elements of music are the structure through which the artist makes his feelings understandable to other people. Let me amplify that statement because I think it will help clear up some of the stylistic questions involved in these discussions of jazz—and it may even shed some light on the murky gloom of the jazz avant-garde. Form is not always necessary for expression. There is a great range of human feeling that can be expressed without language or any kind of intellectual knowledge. Babies cry in pain or gurgle in contentment; men roar in anger or smile in pleasure. Love, hate, fear, and tenderness are basic experiences in the lives of everyone and are communicable in the most direct and universal ways. But, and this is a large "but" in this particular discussion, in order to go further with communication and express the individual idiosyncrasies of human experience, we need a more sophisticated structure and language which is accepted and understood by the expressor and his audience. If this seems to be a rather obvious fact, I can hardly argue the point. However, many have embarked on lengthy discussions of art as if this element of understood language did not exist at all as an intrinsic part of a communicative artistic experience. If we look at this consideration specifically in terms of music, it follows that the musician with the largest musical vocabulary and the most complete control of musical grammar and syntax, can best express the subtle variations of feeling that make up his personality. But here's the rub. Where are the listeners to this music? Are they aware of the artist's language? Do they understand it? Unfortunately, in my experience with the jazz audience, I must admit that they do not. The world of jazz is sadly lacking in educated listeners. Music is a demanding language to begin with. It cannot be well understood without disciplined and dedicated concentration. What has been heard must be accepted and retained in order to understand what is to follow, and there is no going back to catch up. In order to understand jazz, some knowledge and experience with musical formn is necessary. Most of us have that knowledge from our daily lives. It is hardly possible to live without exposure to many different kinds of music. Now what about listening? How about carrying over the results of one experience in order to more fully understand the next one? Labels arid names are conveniences which can serve well to sort out and define, or serve badly to pigeonhole and limit. You don't have to be able to talk about music to be able to appreciate it. The essential kind of educated listening is characterized by a growing recognition of parallel cases, regardless of whether or not one is able to specify one's experiences with labels. When I was in school there was a sign in our rehearsal room that said, "Music is a picture painted on a background of silence." I remember how right I felt about that sign admonishing us to quiet, but as I am writing this now I see an essential concept that was missing from that statement—it is time, as well as silence, on which music is painted. What a fortune of subtleties abound in the .temporal elements of music. How are we measuring musical time? By drumbeats? By clocks? By heartbeats? By instinctive comparison to other temporal experiences? How long is your attention span, you listener to music? Can you concentrate throughout an entire composition or is your attention span limited to a 60-second television commercial? How fine are your perceptions? Have you heard that note before? Was it held longer this time? Has this whole pattern been heard before? These are considerations which we are all taught in secondary school music appreciation class. They are some of the elements which make up musical language. Along with pitch, timbre, and dynamic variations they are the elements of universal musical form. I have been talking in a general way about music and everything I've said is applicable to. Iistening to jazz. Balance and proportion and clarity of thought and expression within a historically understandable musical language are all part of good jazz. But along with these elements, there are some specific characteristics to be found in jazz which give it its special flavor and feeling. |

CLIFFORD BROWN

STAN GETZ

DUKE ELLINGTON

BILL EVANS

|

|

The rhythmic vocabulary of the jazz musician is highly syncopated. Jazz derives much of its impetus from the contrast between the rhythms of the soloists and the generally steady pulsation of the bass and drums. The rhythm section provides measured jumping off points against which the soloist builds a varied pattern of counter-rhythms. The comnlexity and variety of these rhythmic relationships vary with the style—but the process and the essential relationships between soloist and rhythm section are the same for progressive jazz as for Dixieland. The bass and piano or guitar also provide a continuous harmonic carpet on which the soloist walks his crooked miles. This background has a repetitive structure, agreed upon in advance according to the composition being played. This background, moving through time, serves as the springboard for the melodic relationships in the music. This pattern, which keeps everybody playing together, exists in the same essential form and is used in essentially the same way in both modern jazz and in Dixieland; again, with varying degrees of complexity of relationships. |

These, then, are the processes or methods of jazz. Within these methods, there is some improvisation—actually a great deal of it, but generally less than most people, even some highly trained classical musicians, seem to think. And this improvisation is of a sort that is highly disciplined and contained within a given framework of musical "rules." How each musician realizes these "rules" is what makes up his personal style. He may be highly educated and mechanical in his manipulation of musical sounds, or naive and instinctively spontaneous, or highly educated and highly spontaneous, or naive and very mechanical. A high degree of musical information does not guarantee that the holder of this information is able to use it artistically, nor does a lack of musical education guarantee good musical instincts. A great jazz artist educates himself in the best use of the biggest musical vocabulary he can handle and proceeds to fit that vocabulary into the most satisfying frameworks he can find in the most spontaneous possible way, each time he performs. Louis Armstrong, Jack Teagarden, and Barney Bigard have all developed this art to a beautiful degree of perfection. So have Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Lester Young, Clifford Brown, Stan Getz, Miles Davis, and Bill Evans. As a jazz composer, Duke Ellington has created some of the most rewarding pieces of music in America and they stand equally well as songs and as structures for improvisation. Bill Evans has also written many good jazz pieces, each of which has its own special character. Evans' pieces are very defined as structures for improvisations and they retain their unified character even during the improvisations, because each structure is a natural development of one or two musical ideas to which Evans limits himself at the conception of the composition. By incorporating the germinal musical idea into the harmonic structure of the piece on which the improvisations are built, Evans achieves a personality for each of his compositions. |

|

With whom do you agree?

|

Stan Getz has had a great deal of long-deserved exposure in the last three years and is one of the greatest jazz players of all time. He plays the saxophone with an incredible combination of beauty and virility and has one of the widest emotional ranges of any performer I have ever heard. He can project enormous power, generate great heat and excitement, and in the next breath evoke tenderness or a cry of pathos. All this he does while drawing beautifully organized forms, treading that thin line which keeps the natural from sounding banal and obvious, and the spontaneous from sounding chaotic and absurd. In the end, it is not the color of the socks that Lester Young wore at some historic record date, or the personal habits and problems of some troubled musicians, or the eccentric and sometimes anti-social behavior of one or another group of musicians, that make jazz history. Those are the things which require no expense of energy on the part of the listener to understand and are therefore accessible to a great number of uncommitted people. Those things make for idle discussion and momentary attention. It is the artistic content of the music, which requires dedicated digging on the part of the listener, which remains to make a permanent impression on the music of the world. |

|

Original format: 20-page booklet, 9 inches by 12 inches (four pages 9 inches by 6 inches), with a 7-1/4 inch clear flexi-disc bound around the covers. Photo credits: Columbia Records, Carl Iwasaki, Life Magazine, Fred Seligo, Charles Stewart. Numerous photos are omitted here to conserve download time. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|